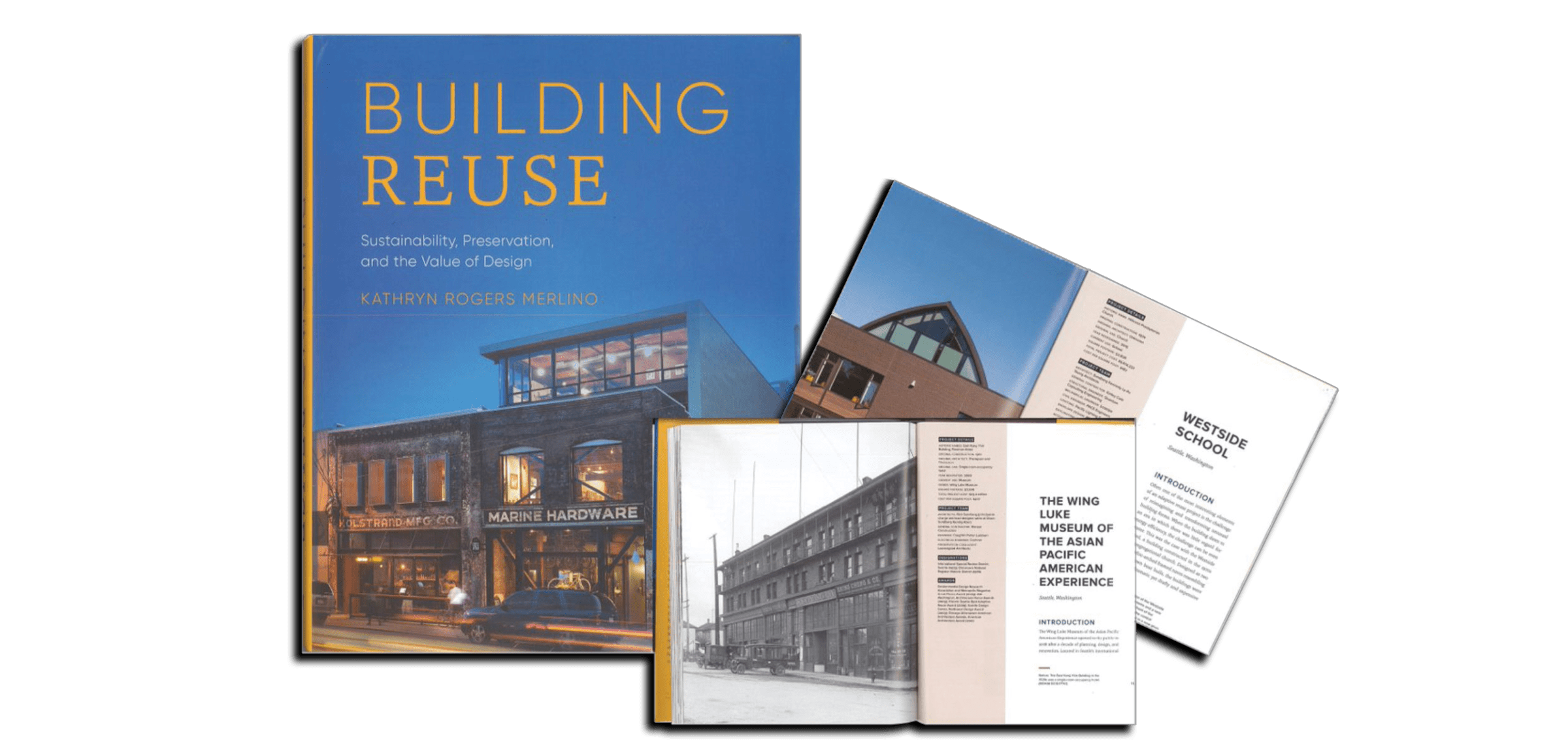

Book Review: Building Reuse: Sustainability, Preservation, and the Value of Design

By Jennifer Mortensen, Outreach Director

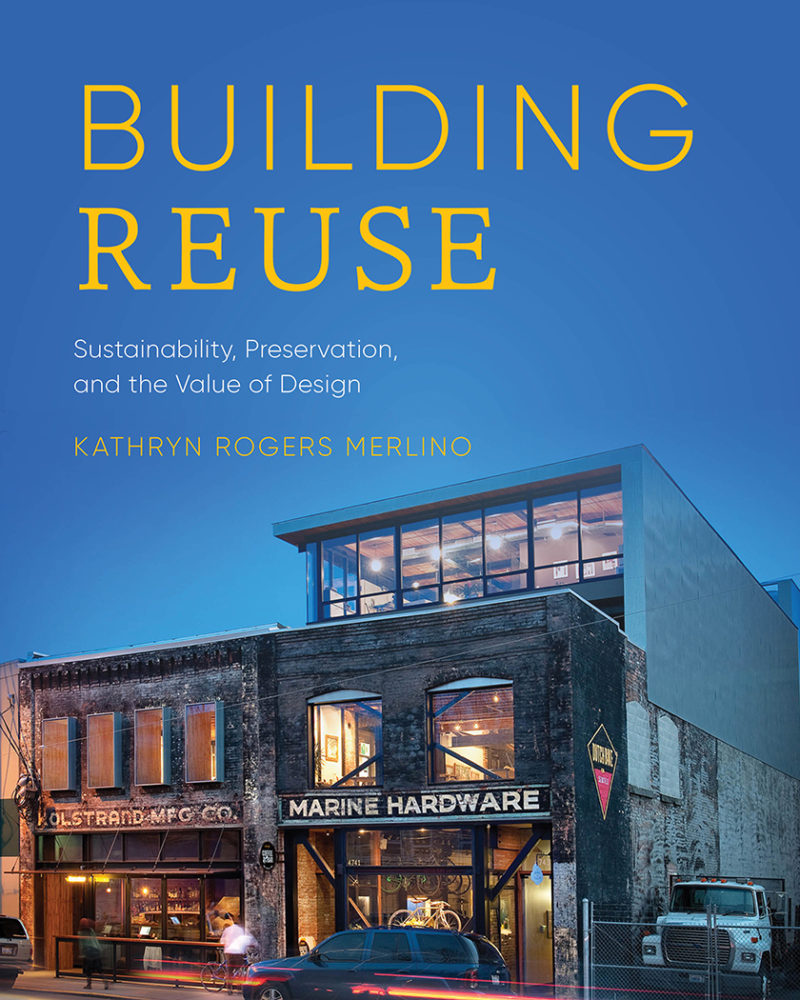

Sustainability and historic preservation go hand-in-hand. In Kathryn Rogers Merlino’s recently published book Building Reuse: Sustainability, Preservation, and the Value of Design (University of Washington Press, 2018), the author ably makes the case with a balance of compelling writing that is backed by both data and engaging case studies.

The book’s core argument revolves around the importance—even necessity—of reusing existing buildings. Rogers Merlino writes that building reuse must be innovative and include a broader range and larger volume of buildings. The book begins by exploring the philosophical elements of why and what we value (and what we should value) in the built environment, guides the reader through the history and parameters of traditional historic preservation policy, illuminates the importance of urban design and character, and only then delves into the metrics and data of building reuse. With this wide-ranging context to support her, Rogers Merlino is able to articulate both the value of historic designations as well as their limitations as an effective sustainability strategy. Ultimately, she argues that we must look beyond historic significance as a reason to reuse buildings:

“Attaching value to buildings exclusively because of their notarized historical significance ignores the fact that all buildings inherently hold value as environmental artifacts. They are repositories of extracted and manufactured materials and represent expended energy and carbon emissions, and as such they hold great value as environmental resources.”

The book dives into the statistics of building reuse, covering building efficiency, initial and recurring embodied energy, strategies and tools for “greening” buildings, the problem of building material waste and debris, and much more. Although there is a substantial amount of data presented in the book (and an excellent collection of references in the endnotes of each chapter), Rogers Merlino never loses her narrative voice, keeping the information accessible and enjoyable to read.

The remainder, and actually the bulk, of the book features thirteen building reuse case studies from the Pacific Northwest, mainly in Washington State: Seattle, Tacoma, Bremerton, Bellingham, Spokane, Walla Walla, and Portland, Oregon. The author gives succinct but rich histories of each case study before describing the design of the building reuse in greater detail. The book importantly recognizes a wide range of sustainability features in those descriptions—some of which a reader might expect, such as preserving original building materials and installing solar panels, and some of which are less obvious, such as project materials being sourced locally and considering a building’s proximity to public transit. While there are certainly repeated energy efficiency strategies used across many of the case studies that results in some redundancy in the information provided, each case study still stands on its own as an engaging read.

Another strength of the case studies is the variety in the type of projects presented. Some projects feature architecturally or historically significant buildings, resulting in a more historic preservation-forward approach. The 1907 SIERR Building at the McKinstry Station, an icon of the industrial architecture of Spokane’s Inland Empire, is a local landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This national recognition allowed the project to utilize the National Historic Tax Credit Program in its financing, requiring a reuse design that prioritized historic details while still allowing for the incorporation of innovative features and modern adaptations. Other projects make more substantial changes to the design of the original buildings, prioritizing performance and making the projects ultimately more sustainability-forward. The 1974 Edith Green-Wendell Wyatt Federal Building in Portland, Oregon, underwent a major rehabilitation which essentially retained only the building’s massive eighteen-story concrete frame, upgrading it with state-of-the-art mechanical systems, energy- and water-saving features, a new glass and steel façade, and a visually-distinctive solar roof.

The range in case studies highlights one of the author’s main arguments, which is that all buildings, by virtue of the energy and materials that went into their construction and their embodiment of a culture, have value and can contribute to a sustainable future by being creatively and innovatively reused. Additionally, Rogers Merlino specifically calls on the architectural design community and architecture schools to be more engaged in the work of building reuse in order to realize that sustainable future. The author writes:

“Redesigning an existing building presents a challenge to the typical design process, and often the best innovation comes from a reconsideration and improvement of the past. . . . With good design and a new environmental ethic of reuse, older and historic buildings can be perceived not as targets for demolition but as sites ripe for reinvention.”

Whether you are new to sustainability as a counterpart to historic preservation or a seasoned professional who knows LEED backward and forward, there is much inspiration to be found in Building Reuse. Each case study represents an astonishing amount of investment, passion, effort, and teamwork over many years, and each set of choices made speaks to the particularity of the individual buildings and their histories. Ultimately Building Reuse describes and demonstrates how good design can enhance a building’s resilience and most importantly reveal and enhance an existing building’s value. Preservation is a continuum, and as such, the lives of buildings have many chapters. It is inspiring to see new chapters being written for such a variety of existing buildings—historically designated and otherwise—with sustainability and innovation at the fore.

Kathryn Rogers Merlino is an associate professor of architecture and the director of the Center for Preservation and Adaptive Reuse in the College of Built Environments at the University of Washington.

The exterior of the 1907 SIERR Building at the McKinstry Station in Spokane

The interior of the 1907 SIERR Building at the McKinstry Station in Spokane

The 1974 Edith Green-Wendell Wyatt Federal Building in Portland, Oregon

Cover of Kathryn Rogers Merlino’s Building Reuse: Sustainability, Preservation, and the Value of Design