Vanishing Seattle: an interview with Cynthia Brothers

The recent threat of demolition of Seattle’s beloved music venue, the Showbox, has captured the city’s attention and launched heated public debate around issues of historic preservation, cultural and community displacement, and public policy. The Washington Trust, alongsideVanishing Seattle, Historic Seattle, Friends of Historic Belltown, and many concerned citizens, is advocating for the meaningful preservation of the Showbox as well as policy changes that will strengthen preservation and help save other important cultural sites. In this interview, the Washington Trust’s Preservation Services Coordinator, Jennifer Mortensen, sits down with Cynthia Brothers, creator of the Instagram project Vanishing Seattle, to discuss the future of historic and cultural sites in Seattle.

Cynthia Brothers, creator of Vanishing Seattle. Photo by Ken Yu.

Jennifer: Give me a bit of background on yourself. Did you grow up in Seattle?

Cynthia: Yes, I was lucky enough to be born and raised in Seattle. My mom came to Seattle as an immigrant, and my dad came from the Midwest. I’ve spent all my life here, except about five years where I was in New York in the mid-2000s.

Jennifer: What made you want to come back to Seattle?

Cynthia: I always knew I would come back to Seattle because that’s where home is, my home base, and my social support network.

Jennifer: Why did you start Vanishing Seattle? Was there a specific place that sparked the idea?

Cynthia: I started Vanishing Seattle on Instagram in January 2016. I think living in New York primed me in some ways for it, seeing the vast amounts of money and wealth side by side with eviction and displacement. Then I came back to Seattle and started to see some of the same things happen—seeing how all this new wealth pours in and changes things, seeing a lot of my friends getting pushed out. What actually prompted me to start Vanishing Seattle was a Filipino restaurant on Beacon Hill called Inay’s where my friends and I liked to go. One of my friends, a drag performer named Atasha Manila, would do this epic, three-hour, one-woman drag show every Friday, and there would always be tons of people there. It was incredible. But because it was in North Beacon Hill, an area that’s been gentrifying pretty rapidly, the rent was raised. The owner of Inay’s decided he was going to have to close. I was there for the very last night, which was Atasha’s last performance at Inay’s. She performed Effie’s song from “Dreamgirls,” “I Am Telling You I’m Not Going.” I was taking pictures and recording it. To me, that moment in that space was really unique and special. It was a cross-section of the Beacon Hill community, the Filipino and Asian community, the queer community, and it was a place that was uniquely Seattle. You can’t replicate that. These are the types of places that we’re losing. I had this need to capture that and share it—to post it on social media as a way of saying, “Look! This is an awesome Seattle space and community, and we’re losing it.” From there I kept posting every day, trying to capture different spaces that are disappearing, and it just took off.

Jennifer: What types of places do you feature most? Are they mostly businesses, community centers, or all of the above?

Cynthia: It’s a mix of places. I do feature a lot of small businesses, community institutions, churches, homes. I’m trying to capture as much as I can—a holistic reflection of places that are going away. The problem is, I cannot keep up. Even if I only focused on the small businesses that are going away, there’s a huge backlog. I can’t keep up. People send me a lot of stuff, which is great, because I don’t always know what’s going on and there are places that I’m not as familiar with or haven’t been to. People send me pictures, stories, and memories, and I include them in my research and my write-up. I think that’s great because it’s this city of voices, describing all the different places people love that are going away and why they matter. I think Vanishing Seattle should be a collaborative storytelling effort. My experience is just one experience, so I love it when people send me stuff and when they comment on posts—when people respond to each other, share stories, and connect online. For me, that’s the coolest part because it reinforces that these places mean something to people.

Jennifer: The name “vanishing” straddles the line between “about to be gone” and “gone.” Your content also does that. Was it intentional or just kind of a happy accident that your name plays in both worlds?

Cynthia: I was just trying to find something that sounded good and wasn’t already taken on social media. The “Vanishing Seattle” thing—it’s not like I came up with that idea. After I started the account, I found out there’s a book called Vanishing Seattle published by Clark Humphrey in 2006. I think there’s also a “Vanishing New York” and maybe a “Vanishing San Francisco.” I had someone from Boise contact me to ask if they could do a “Vanishing Boise,” and I was like, “Yeah!” If someone wants to start it in their own place, under the same theme, reflecting what they’re experiencing in their community, more power to them. This theme of change and displacement—it’s not just happening here. It’s happening everywhere in urban areas. And it addresses some real underlying social and political problems.

Jennifer: What do you hope people learn or come to appreciate through Vanishing Seattle?

Cynthia: One of my goals is to cultivate an awareness and appreciation of Seattle places and how they are inseparable from Seattle’s history, culture, and communities. Those places don’t always have to be monuments from the history books. It’s about capturing all the cool things that are in some ways reflective of a community that used to live here. I hope that people will just pay attention and appreciate and learn and listen.

Jennifer: You’ve talked before about your project not being about nostalgia but of being about equity. How do you feel like preservation can help the cause of equity? Do you feel like preservation has the power to be part of that process, be a part of the effort?

Cynthia: Absolutely. One example is Washington Hall and how that was an important cultural and community space for so many different immigrant communities and communities of color in Seattle history. Historic Seattle rehabilitated that place, saved it from demolition, and now it’s occupied and managed by different nonprofits and arts groups and continues to be a community space. That is a clear example of using preservation to save and maintain a place that was significant culturally and for the community. I think a lot of people think preservation is this vacuum that’s devoid of social significance. That is a belief we need to challenge. At its core, preservation is about “what do we care about?” What are the places and the communities attached to them that we want to prioritize and support because they’re important to us? Yes, it’s about buildings, but what do those buildings enable or facilitate? What’s happening inside those spaces that is important and equitable? The answers to those questions involve people, culture, legacy, history—all this stuff that goes beyond the question of who the architect was.

Jennifer: Do you feel like you’ve witnessed an increase in awareness over the last two years? Are more people seeing that places are disappearing and it’s a problem that needs to be addressed? Have you seen that translated into direct action?

Cynthia: That’s my hope. When I started Vanishing Seattle, I did not expect that it would resonate with people. I think it has succeeded through a combination of timing and hitting a nerve with what people were experiencing. Often when these important places disappear, it can be a really isolating experience, because at its core it’s about loss—loss of community, history, people you care about. My hope is that through Vanishing Seattle, people can come together in a proactive way and feel affirmed, in the same way that I felt affirmed when Vanishing Seattle built this momentum and people started responding to it. For me, it confirmed that I am not alone, we are not alone, we are all experiencing it, and we recognize at some level that this is unjust. I don’t want people to be discouraged because of a constant barrage of change. I want people to get more engaged—whether learning more about advocacy and how they can make their voice heard or making art or connecting with other people or with organizations—so no one can say that these places disappeared unnoticed and disregarded.

Jennifer: Have you been involved in any other specific campaigns before the Showbox? Were you doing this kind of work before or is this new territory for you?

Cynthia: If there’s a grassroots effort or campaign that exists, I will share it, to try and help get more eyes on it, amplify it. I think the Showbox is definitely one that I’ve gotten a little deeper into, being a co-nominator [for its city landmark status], but a lot of my role is amplifying the movement online. There have been other cases where, for example, I worked with the Friends of Historic Belltown on the Griffin Building and the Sheridan Apartments. I posted on Vanishing Seattle about those buildings and got a lot of responses. One of the commenters was Ben Gibbard of Death Cab for Cutie, who is now very involved with the Showbox campaign. He commented that he once rented a studio apartment at the Sheridan, where he wrote most of the album Plans, including their best-selling single “I Will Follow You Into the Dark.” In the course of these campaigns, I coordinated with Friends of Historic Belltown to lay out a couple of steps for people—about who you can email, how you can show up to these landmarks review meetings. We also worked together to compile materials to email to the [landmarks] board, making the case of why the Sheridan is important to local music history, for example. When the Sheridan and Griffin were designated, it showed that when the public gets involved, when stories come out that connect a place to Seattle history and culture and make a case for why it’s significant—that makes a difference. I think it taught people about the process, the options they have, and showed that you can effect change. People are hungry for information about what they can do and for some affirmation that when they fight for something, they can win.

Jennifer: A captive audience is powerful. Just pushing it out there and publicizing it has a huge effect.

Cynthia: I want people to know that you don’t have to be a policy expert. Sometimes you just have to show up, get your voice in there, participate in the democracy. With the Showbox, there is a massive groundswell of people involved, which is how it should be. There are ways that you can participate without being intimidated by the rigmarole and the process. The process is not accessible, which is a shortcoming. But we don’t have to accept it. We can blow that up. We can subvert it.

Jennifer: That’s exactly what the Washington Trust and Historic Seattle are here for. We are eyeballs deep in this stuff all the time and so we can say, “This is what we can do, this is the process, these are our options, and this is our strategy.” We understand all that stuff so that you don’t have to. You can just say, “This is a place that I’m concerned about, this the outcome I’d like, what are our options, what can we do?”

Cynthia: That’s great for me too because I can point people towards local organizations if they want to help or volunteer, if they want to know how to get more engaged. I’m not an expert. I’m just trying to give people more options or point them towards resources or groups if they want to go that route. For me, with any movement, “let a thousand flowers bloom.” If I can facilitate making connections, get information out, or make people feel like they can make a difference, that’s the role that I would like to play, without dictating what it needs to look like.

Jennifer: What’s your personal experience with the Showbox and why do you think it is so important for Seattle on a community and social level?

Cynthia: I used to play in bands myself, never at the level to play at the Showbox, but I understand, as someone who played music and someone who enjoys music, the role the Showbox plays in our musical landscape and ecosystem. Around the country and the world, Seattle is regarded and promoted as a music city—even the City promotes itself as a place of great musical heritage. What does it say about where we are now when one of the crown jewels of our musical history, culture, and community is up for sale to the highest bidder, in exchange for more luxury housing that no one who works at the Showbox could afford? We’ve experienced all these losses, and now it’s come to this? That was where a lot of people were like, “Enough is enough,” and started coming together. I’m optimistic that this movement is an opportunity not just to save the Showbox but to change the system that has allowed things to get to this point. If we don’t change the system, we’re going to be fighting the same fight over and over. The Showbox has been lifted up as this iconic place, which it is, but that shouldn’t overshadow the fact that there are many other places in our musical ecosystem that have either been lost or are extremely vulnerable. Many of these performance spaces, especially in lower-income communities and communities of color, don’t get the same kind of visibility. So the Showbox movement isn’t just about saving one place. You don’t have to know anything about preservation or policy to understand that these places mean something to people in their everyday lives, which is why the Showbox has been so galvanizing.

Jennifer: Do you have any ideas about how the system can change? Or are you interested in just opening up the conversation and seeing what the options could be?

Cynthia: I’m not a policy expert, although I’m trying to learn more. I’m more concerned with opening up the conversation. There are immediate, medium-term, and long-term tweaks to policy that can happen, but the larger questions still need to be addressed. What is happening in the underlying system that’s allowing this destruction of cultural spaces to be perpetuated over and over again? What is it about the fact that we’re being dominated by real estate speculation, and what are the failings that we’re seeing as the result of hypercapitalism? Are there alternative models that we need to look to that involve public ownership, community ownership, different ways that we can own land, to keep places as community assets? Where it’s not just about relying upon the “free hand of the market,” because that doesn’t work for most people. These questions are getting into larger systemic stuff, but I feel like we need to make some hard policy choices about what we value and whose needs we are prioritizing. For me, it’s about poking holes into assumptions about progress, what that looks like, and just raising questions, so people don’t just swallow the narrative that this is all inevitable, just a part of progress or change. Because it’s not. We have the power to shape what kind of city we want to live in, and that’s really the moment that we’re in now.

Jennifer: What’s next for Vanishing Seattle? Do you have any big plans in the works or are you just planning to continue the good work you’ve been doing?

Cynthia: I definitely want to keep documenting things in the same way that I have been. One project in the works is a Vanishing Seattle short film series, which is in pre-production right now. The idea is to delve more deeply into the stories of community institutions and important places that people care about which are potentially vanishing. We’re working with different filmmakers who all wanted to do stories about places and communities they’re connected to. Hopefully we’ll have some films ready for distribution sometime next year.

Jennifer: Did you get a lot of artists volunteering time for that project?

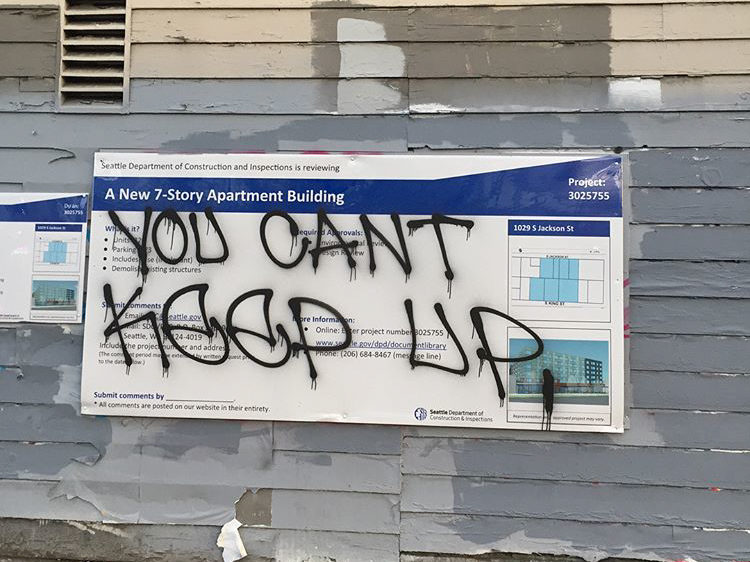

Cynthia: I received a grant from 4Culture, and I also had a Vanishing Seattle pop-up at Pike Place Market earlier this year at the Eighth Generation space. We worked with Eighth Generation to make our own Vanishing Seattle-themed products and also worked with local street and graffiti artists to put their art on products like t-shirts and totes. That was paired with an exhibit featuring a big wall display of images and quotes pulled from the Instagram account. In the exhibit there were prompts like “What do you miss about Seattle?” and people could respond with Post-Its. It filled up the entire wall. There were comments like “I miss feeling safe on Capitol Hill” or “I miss my friends.” It was about people’s sense of well-being and supportedness, being able to afford living in this city, and feeling safe and protected. Some of the revenue from product sales at the pop-up is going towards the filmmaking project too, and we’ll keep fundraising for it.

Jennifer: The Washington Trust’s audience is statewide, but I think this idea of losing meaningful places will resonate with people across the state, even if development elsewhere is not quite as accelerated as it is in Seattle.

Cynthia: There’s a ripple effect. I know it can be annoying to be so Seattle-centric, but this is really a regional issue. What happens in Seattle is being felt in south King County, in Snohomish and Pierce County, in Tacoma, even in Idaho and other states. And we need to tell new people that they can come and participate in this stuff. We need your help—we want you to pay attention and understand why these places are important. Why did you move here? Did you move here because you want to find community or because you’re interested in Seattle and its places? Can you use your voice and your efforts to connect with people and to help people save the places they care about? Can you be an active contributor to this ecosystem? We’ve always been a city of transplants. But now, are we building a city that caters only to people who have a lot of money and privilege? Or are we still a place that’s welcoming to immigrants, refugees, the working class? I don’t think so. I don’t think my parents could have come to the Seattle that is here now. In the end, it comes down to values and how we want to live collectively and take care of each other.

Thanks so much to Cynthia Brothers for sitting down with us! Support Vanishing Seattle by following along on Instagram, or donate to the upcoming Vanishing Seattle film project at vanishingseattle.org.