Being Relevant

November 1, 2018 | 5:03 pm

from Washington Trust

Recognizing cultural value as a component of historic preservation

For over four decades now, the Washington Trust has worked to cultivate a community that values saving historic places and also understands the need for representing historic preservation on a statewide level. Our community understands that preserving and reusing historic places is an important part of any town or city’s history and identity, but historic preservation still sometimes struggles to remain actively relevant in everyday lives.

If we are going to help historic preservation become more relevant, then we must get beyond the assumption that everyone should inherently understand that historic buildings are valuable and should be preserved. We must be able to articulate compelling, specific answers to questions like: Why should we preserve? Why do historic buildings matter? These are basic questions, but ones that are important to regularly address and clearly express.

One of the most common answers I hear from community members as to why it’s important to preserve buildings is because they provide spatial experiences which cannot be replicated with photographs or new construction. When making this argument, historic building advocates will call out not only the visual experience of a building’s design, architectural details, and patina, but also how experiencing the space of a building viscerally connects modern users to the past generations who built, used, and loved that building.

This rationale for preserving buildings—that experience is a foundational method through which people find value in historic buildings—is unfortunately not reflected in the regulatory framework of preservation. The concept of experience, and by extension the concept of use, are not elements that factor into the city ordinances and historic registers that offer both public recognition and protection to historic places across the state and the country.

By and large in the United States, the criteria for listing on a historic register revolve around the merits of its design; its relation to a historic figure, event, or trend; or its physical siting within a city or neighborhood. What’s more, all criteria, even the criteria that do not specifically relate to the physical aspects of a building or place, are evaluated almost exclusively through a building’s physical features. How this is often described in practice is that a building or place must possess the “ability to convey its significance” through physical integrity. This makes it very difficult to officially recognize or protect buildings that have undergone significant changes, places that are valued by a community primarily for cultural reasons, or places that do not involve buildings.

This system, by its nature, unfortunately distances today’s communities from historic buildings by implying that the connection one may currently have to a historic building is inherently less important than the past of that building. Elevating the past through a building’s physical traits in such an exclusive way can delegitimize present-day experiences and values. This is not to say that historical figures and events should not be recognized for their significance, but how are we to expect people to develop a meaningful interest in and a desire to save buildings unless they have a personal, meaningful connection? Why can’t historic preservation make room for recognizing the current cultural and social value of historic places in addition to, or perhaps in some cases regardless of, the reasons it was built historically?

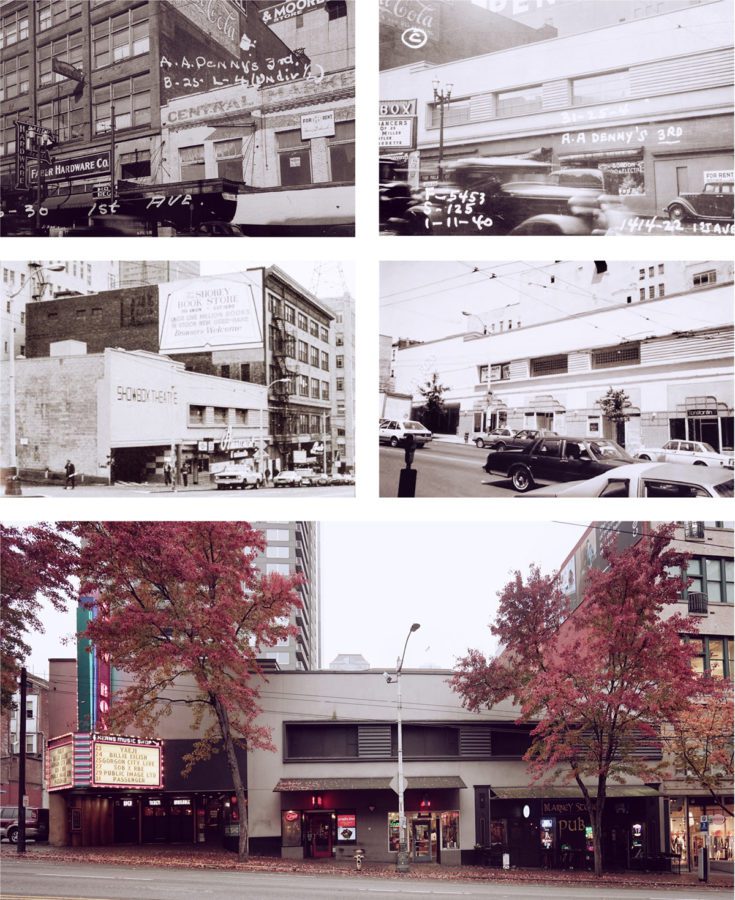

An interesting example of this issue is making its way through the City of Seattle Landmarks program right now: the Showbox. Completed in 1917, the building was originally built as the Central Public Market, a competitor to the nearby Pike Place Public Market. In 1939, the building underwent a substantial Art Moderne remodel and opened as a performance venue, “The Show Box.” For the next 80 years, the building continued mainly as a performance venue, with brief stints as other ventures and a few periods of vacancy.

The period of history most people will personally remember the Showbox for began with a new management company taking over the venue in 1979. The Showbox began to feature Punk Rock and New Wave-era bands, eventually becoming the premier rock venue in the city. In the 1990s, the Showbox also held comedy shows in addition to continuing to nurture Seattle’s growing rock scene. The Showbox has changed management several times in the recent past, but it continues to be a pioneering music venue and a key feature of Seattle’s identity as a music city.

The many faces of the Showbox. Top left: the Central Public Market building in 1938; top right: The Show Box in 1940 after the Art Moderne remodel; middle left: the Showbox in 1981; middle right: the Showbox in 1987 after a substantial storefront remodel; and bottom: the Showbox today. Historic photos from Puget Sound Regional Archives and the University of Washington Special Collections, accessed through the Showbox Landmark Nomination document.

As the Showbox goes through the City of Seattle’s landmarking process, it will be interesting to see how the building’s “period of significance” is defined and how the Seattle Landmarks Board interprets the existing physical traits of this building. The original exterior was almost completely covered with the Art Moderne remodel, and while that remodel is now historically significant in its own right, the marquee and the storefronts have been reconfigured and changed several times since 1939. The Landmarks Board will almost certainly look at each of the physical details of the building, discuss the numerous changes and when they occurred, and debate whether or not those physical features are able to “convey the significance” of the Showbox.

Given Seattle’s current preservation ordinance, this focus on physical traits is a constraint under which the Board must operate. Unfortunately, this approach seems almost completely beside the point of why most Seattleites would consider the Showbox a historically significant place. For most Seattleites, the Showbox is important not because of the marquee or the façade, but because it has been a cultural gathering place for decades. The Showbox has fostered, and continues to foster, the music scene in Seattle and is undoubtedly the site of many formative experiences for those who perform and attend shows there. This cultural value—the Showbox’s continued and ongoing importance as a community and art space—has no bearing on the landmarking process with our current system.

This disconnection from the Seattle community of today, the community we will be asking to stand up in support of landmarking the Showbox, stems from this hyperfocus on physical traits, but also from the fact that in preservation buildings generally have to be over 50 years old and the significance must also be over 50 years old. The present significance of a place and its amount of cultural value to the present community are unfortunately not factors in the landmarking process. Fifty years is the national age threshold for historic preservation, which most local municipalities have adopted, but in Seattle the local threshold is actually only 25 years. The significance for Seattle landmarks can be as recent as 1993 by that standard, which bodes well for the Showbox. This time period will include the first waves of rock music starting in 1979, of which some people in the existing community still have personal memories, but again, the Showbox has undergone significant physical changes within the past 25 years.

The issue stands that our current system for historic preservation implies that when it comes to a historic building, its past is inherently more important than its present. This goes against a core philosophy of preservation that the Washington Trust has been trying to promote, that the best way to preserve a building is to use it, maintain it, and care for it. Our movement cannot afford to continue to overlook, and by extension alienate, the users, owners, stewards, and community members who are doing the important work of making historic buildings useful and relevant today. It is ironic that historic preservation is often promoted as beneficial because there is value in experiencing a place rather than just looking at a photo of what was, while at the same time we disregard the human and social experiences of now as worthwhile measures of a place’s significance. If we want to make preservation more relevant to people today, we should start by making today more relevant to preservation.

A lively crowd for a Macklemore & Ryan Lewis concert at the Showbox. Photo by Dave Lichterman, “lavid” via Flickr.

Some might think this approach could dilute historic preservation to the point where anything could be listed, making recognition effectively meaningless. On the contrary, cultural values and the significance of a contemporary use can be recognized and rigorously evaluated in much the same way that traditional historical or physical values are currently evaluated. By analyzing the depth or strength of a place’s cultural value, the length of time a place has held cultural value, and how it compares to other similar places of cultural value, this potential criterion of significance can be as thoroughly and properly vetted as would a traditional idea of correlation to historical events or persons.

There have been some efforts in the United States toward recognizing cultural values through historic preservation. Traditional Cultural Properties (TCP) are properties eligible for inclusion in the National Register based on associations with the “cultural practices, traditions, beliefs, lifeways, arts, crafts, or social institutions of a living community.” TCPs are specifically geared toward recognizing these traits in living communities; not only is the physical integrity assessed (“location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association”), but the integrity of the place’s relationship to the existing relevant community is also a factor. A TCP must still be a physical place as intangible resources are not eligible for the National Register, but these more inclusive concepts are important to incorporate into preservation efforts on a broader scale. Unfortunately, TCPs are not well understood by the general public and these more inclusive concepts have not been very widely adopted into local register frameworks.

One local preservation program in Washington, however, recently adopted a great example of an inclusively-worded historic register criterion. As of this past February, the Spokane Register of Historic Places may include a property that “represents the culture and heritage of the city of Spokane in ways not adequately addressed in the other criteria, as in its visual prominence, reference to intangible heritage, or any range of cultural practices.” Potential Spokane landmarks in this category are still subject to the 50-year threshold and the physical integrity issue, but the Spokane Municipal Code does allow room for integrity of “association” which can potentially have more broad application. This criterion represents a much-needed step forward in acknowledging cultural values that may fall outside of the traditional notions of historic preservation.

The entire field of historic preservation would benefit from an expanded approach to places worth saving because it would allow a more diverse and relevant group of stories to be shared and for more people to be engaged. For the Washington Trust, a discussion in which we asked ourselves “why”—why should we preserve? Why do historic buildings matter?—kept leading back to one key concept: community. Every answer we have come up with for the question of why historic preservation matters revolves around the idea of building, supporting, and sustaining communities through historic places. Visual diversity and uniqueness in architecture help build and support community identity. Historic preservation is a sustainable practice that supports good, human-scale urban planning and the protection of community assets and resources. Preserving history and experiences through the built environment can create a sense of continuity and belonging for community members.

If historic preservation really is all about building, supporting, and sustaining communities, then it has to be about more than just examining the physical elements of buildings. If we are going to make preservation relevant for the communities of today—the people using and experiencing buildings now—historic preservation must better reflect why historic places are valued today. There will always be the means in historic preservation to preserve a building for the sake of architecture, but it’s time now to make room for preserving buildings for the sake of people.