A cathedral of science: creating a photography exhibition for the 75th Anniversary of the Manhattan Project

January 25, 2019 | 4:05 pm

from Washington Trust

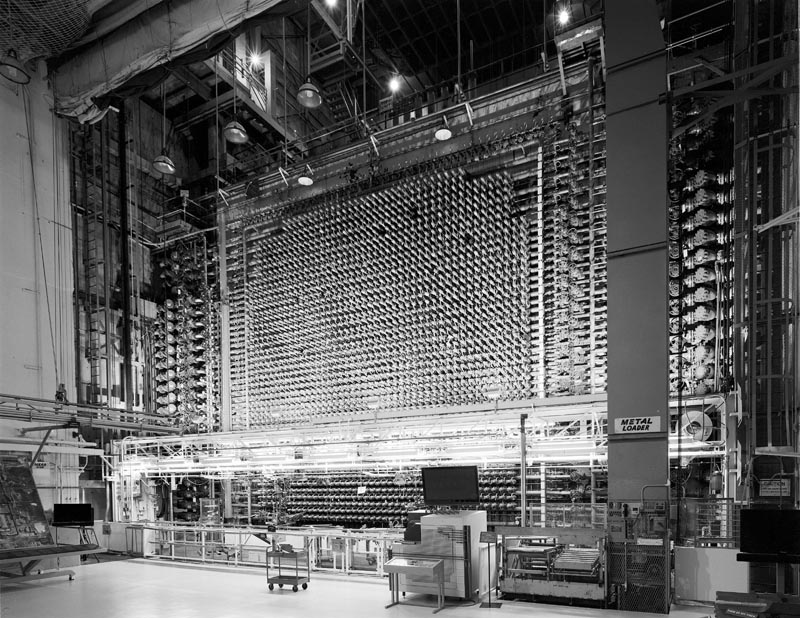

The loading face of B Reactor, the world’s first full-scale nuclear reactor.

By Harley Cowan

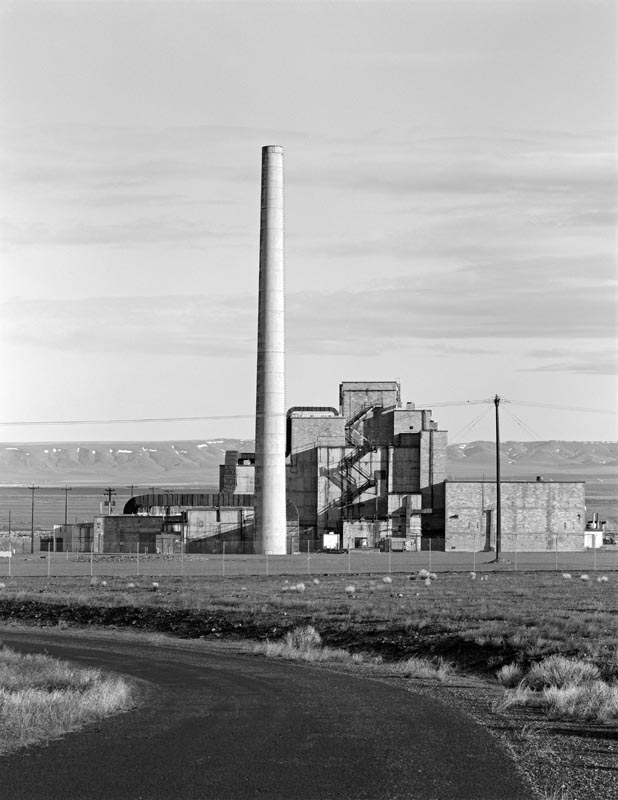

I grew up in Richland, Washington, next to the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. In March of 2017, as part of a research fellowship on heritage documentation, I had the opportunity to spend a week photographing the newly established Manhattan Project National Historical Park. I was there to make a contemporary record of B Reactor (1944), the world’s first full-scale nuclear reactor which produced plutonium for the Trinity Test in New Mexico and the Fat Man bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan. Arguably the greatest engineering feat of the 20th century, and the most terrible, a Promethian altar of science, the B Reactor has long held a fascination.

So what is heritage documentation?

Following the Great Depression, Roosevelt’s New Deal created a number of make-work programs including the Works Progress Administration, the Farm Security Administration, and the Civilian Conservation Corps. Since 1933, the National Park Service has administered one such program, the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), which documents and catalogues American architectural heritage through written histories, measured drawings, and photographs. While most New Deal-era programs no longer exist, HABS remains active. In 1969, the National Park Service added the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) to record infrastructure, machinery, and industrial history. In 2000, its scope of conservation was expanded again with the Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS). Together these three are our nation’s Heritage Documentation Programs. Their archives constitute the most accessed records in the Prints & Photographs Division of the Library of Congress.

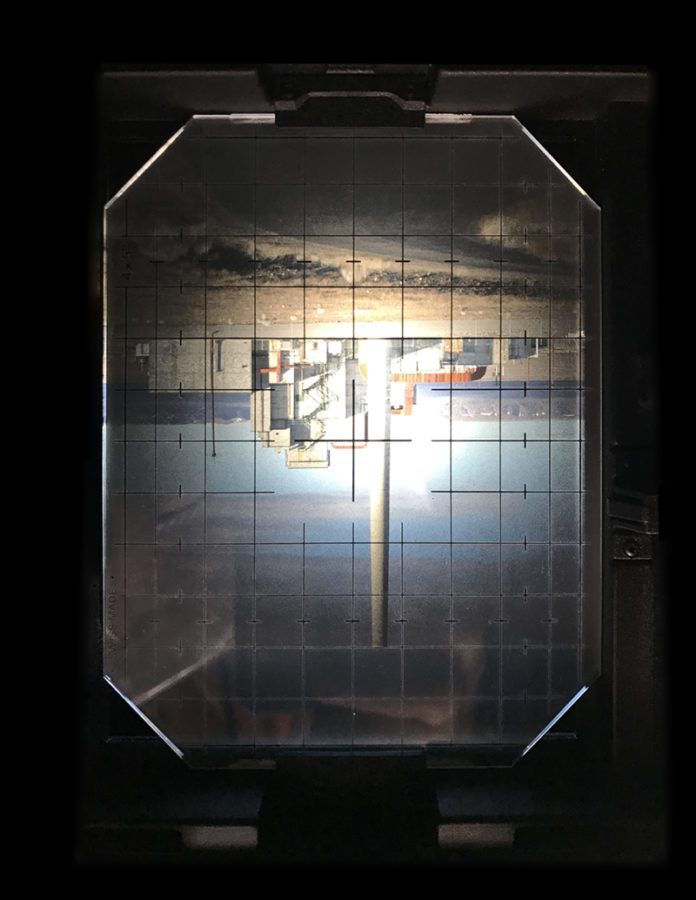

To satisfy the strict requirements of the programs, the Secretary of the Interior laid out standards for photographic documentation which include the use of a large format camera and black and white film. The smaller format cameras most people are used to have a lens centered on and perpendicular to the film or digital sensor. With the large format camera, the lens and the film are connected by a flexible bellows allowing each to be positioned independently. This provides the required in-camera control over perspective and the plane of focus. Additionally, to meet the 500-year archival standard of the Library of Congress, black and white sheet film is used and is processed by hand.

Photographing B Reactor from a distance with a large format camera. Photo by Harley Cowan.

The view through a large format camera.

It was with these parameters that I set out to document the B Reactor and environs. Nothing like B Reactor had ever been built before; interpreting its engineering, major systems, and methods of construction was no small feat, especially with only a few days to do so. Fortunately, there were a few things working in my favor: I had visited B Reactor before; I had worked in nuclear industry through high school and college; I am a practicing architect and laboratory planner; and I was a student at the Pacific Northwest Preservation Field School, a program in the theory and practice of historic preservation through University of Oregon.

To access the site, I went through a background check to receive my security clearance and identification; portions of the national park are still within the secure boundary of the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. Each day it was about an hour drive from Richland to B Reactor, and I would have to stop and be processed at a secure gate. The Hanford site is a kind of wildlife preserve. Only a small fraction of the land, which is half the size of Rhode Island, has been disturbed by construction. Large herds of elk and deer roam throughout, and it is not uncommon to see rabbits, geese, quail, coyotes, and porcupines.

While on Hanford Nuclear Reservation, I had the unexpected pleasure of access to the pre-Manhattan Project sites that are part of the park, including Hanford High School (1916), the Allard Pump House (1908), the White Bluffs Bank (1909), and the Bruggemann Ranch (1907) which was designated by the Washington Trust as one of Washington’s Most Endangered Places in 2018. In the limited time, I was able to take a few general shots inside and out of each building. The floor of the last remaining building at the Bruggemann Ranch is littered with timber and roofing, nails, spark plugs, and rabbit bones. Barn owls were in residence at both the high school and pump house. The bank, the only structure remaining of the town of White Bluffs, was being rehabilitated and afforded me the unusual opportunity to capture pictures of construction work in progress. These kinds of visual records can be extremely valuable to future historians and preservationists.

The White Bluffs Bank (1909) is the only building remaining in the abandoned town of White Bluffs. The existing wooden window frames and sashes, thanks to the desiccating climate, were mostly salvageable and were repaired and reglazed. Photo by Harley Cowan.

The last remaining building at the Bruggemann Ranch (1907) on the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. West and south façades shown. Photo by Harley Cowan.

My visit to the B Reactor occurred outside of the normal tour season which was important in order to make photos without interruption. The public is allowed on the grounds around the site and in most of the ground floor spaces within the reactor building. Some areas like the valve pit are off limits due to their industrial nature, and a few places like the reactor core itself and its control rod and safety rod rooms remain monitored as radiological zones.

The building is roughly a three-tiered ziggurat with most spaces spread out around the reactor in the first tier. The graphite core and control rods occupy the space at the center and up into the second tier. Safety systems sit above the reactor in the top tier. Hidden below grade is a twenty-foot-thick concrete slab. The exterior is a combination of cast-in-place concrete for mission critical elements and reactor core shielding, while concrete block and concrete brick masonry were used in less sensitive areas for expedience of construction. While utilitarian in nature, the shape and sequence of spaces create a dramatic reveal. One enters through a normal-looking door in a block wall and walks through a wide corridor with a concrete floor and block walls painted green and white. Ducts and pipes run overhead, also painted white. Green wooden doors line either wall opening into rooms, shops, and lavatories. At the end is a similar pair of doors beyond which the space opens out and rises up, cathedral-like. Turning to the left, you are confronted by the expansive, lighted face of the reactor, the ends of its 2,004 process tubes arranged in a grid with enormous standpipes flanking each side and branching off into a rhythm of valves and fittings.

The exterior of B Reactor (1944), showing its resemblance to a ziggurat. Photo by Harley Cowan.

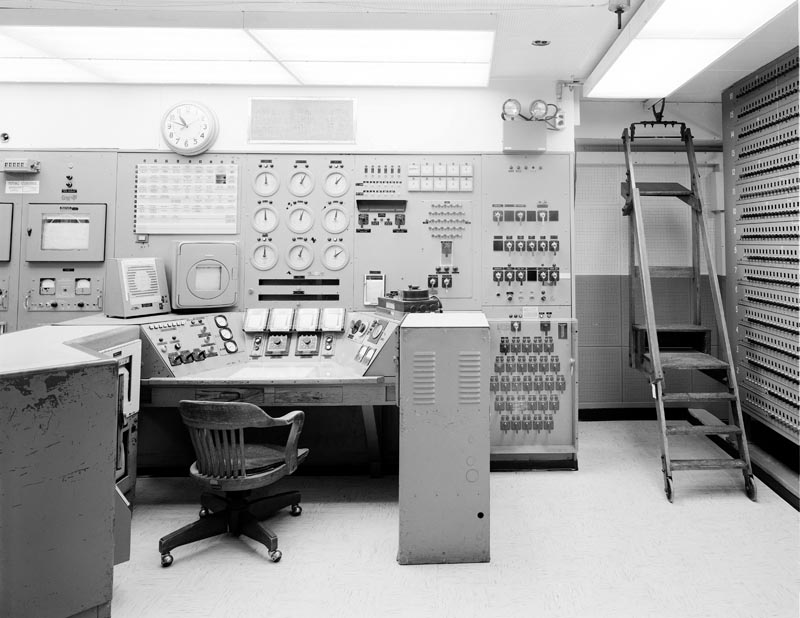

I spent the next few days exploring the rooms and corridors that are open to the public including the control room, radiation monitoring lab, accumulators and their enormous ballast tanks, electrical and ventilation equipment rooms, the instrument shop, and Enrico Fermi’s office.

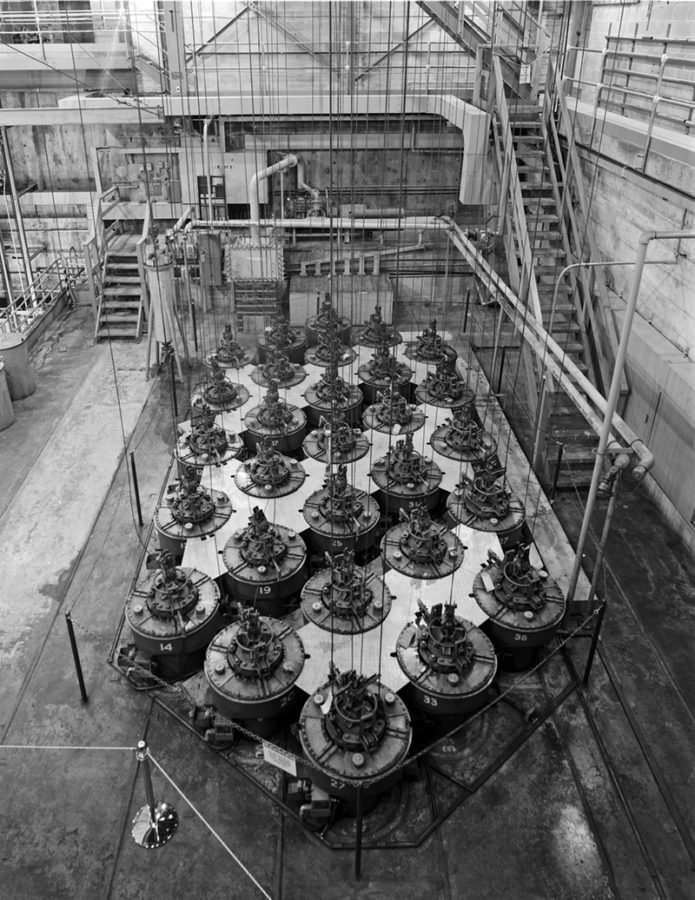

On my last day, we (myself and two staff from Mission Support Alliance, the stewards of B Reactor) entered the radiological zone to photograph the safety systems which sit above the reactor. The health physics technician performed a Geiger counter check on each of us, along with the camera gear, after which we put on personal protective equipment (PPE) and climbed several steep flights to a room not on the tour route in the upper portion of the ziggurat. During the reactor’s active operation vertical safety rods, long metal tubes filled with boron, were suspended aloft by cables. In an emergency, they would release dropping by gravity into the reactor shutting down the chain reaction by absorbing neutrons. Today, these rods have been permanently lowered into the core.

Above the top of the core, we set up on a narrow metal catwalk with pipe railings—not easy with a large format camera. There was not enough room to fully open the tripod. Framing and focusing the image proved to be a challenge. I took four shots but only the first turned out. Unbeknownst to me at the time, the tripod settled slightly, throwing the focus off for all but the first sheet of film. We packed up and hauled out, with a very brief glimpse at the discharge face of the reactor on the way back down. Another Geiger counter check confirmed that we had followed our protocols and were free to return to the public side of the building where I packed up my gear and drove off the Reservation for the last time.

The vertical safety rods of the B Reactor which were used to rapidly shut down the chain reaction in an emergency. Each circular hopper contained a sixty foot long safety rod which, during operation, would be suspended by the cables up above the reactor core. Today, these rods have been permanently lowered into the core. Photo by Harley Cowan.

A public exhibition of silver gelatin prints will be on display at Allied Arts’ Gallery at the Park (89 Lee Blvd.) in Richland from March 5 through 29, 2019, with an opening reception to be held on Friday, March 8 from 6:00-8:00 pm. The show will largely feature photography of B Reactor and its engineering and construction, but will also include the Bruggemann Ranch, the Allard Pump House and canals, Hanford High School, and the White Bluffs Bank.

To view more photos of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park visit:

https://www.harleycowan.com/manhattan-project

To read more about my visit to B Reactor visit:

https://www.harleycowan.com/blog/2017/7/4/a-cathedral-of-science

Looking at the underside of the ballast tanks and the connection to the accumulators. 4×4 wood posts provide a “soft brake” if the ballast tanks were to crash down in an emergency. The system pumps are in the background. Photo by Harley Cowan.

A hand-painted, wooden warning tag prevents workers from closing a cooling system valve at the loading face of the reactor.

The reactor operator’s console and scram panel within the Control Room inside B Reactor. The clocks have been set to the time when B Reactor went critical on September 26, 1944, marking the world’s first self-sustaining chain reaction. This chair is an original, although a different chair is placed here during tour season.