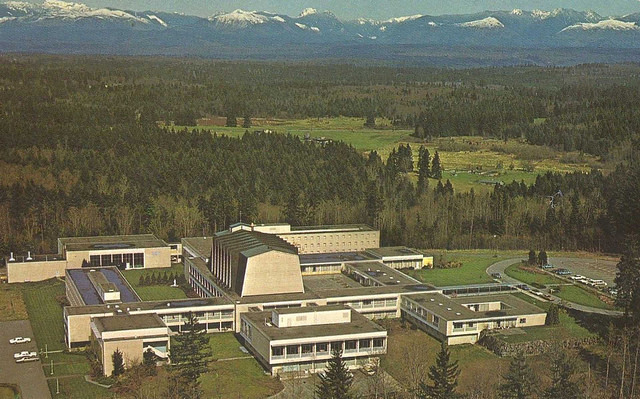

Following World War II, nuclear engineering programs proliferated at universities across the country, including the University of Washington (UW). Retaining a competitive Nuclear Engineering program, however, required construction of a research reactor. Designed in 1961 by The Architect Artist Group, known as “TAAG”, the Nuclear Reactor Building was a unique collaboration between the architectural and the engineering departments of UW.

Efforts to save the building from demolition in 2008 culminated in the nomination of the building to the Washington Heritage Register that same year and the National Register of Historic Places in 2009. Though younger than the minimum of 50 years that is generally required for listing, the Nuclear Reactor Building (constructed in 1961) was placed on the National Register of Historic Places because it demonstrated exceptional importance with its association with significant historic events, embodying the characteristics of the Modern Movement and representing the work of prominent Northwest architects. The building was also placed on the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation’s 2008 Most Endangered Historic Properties List. The earlier advocacy efforts involved the Friends of the Nuclear Reactor Building (consisting mainly of University of Washington students), Docomomo WEWA, Historic Seattle, and the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation.

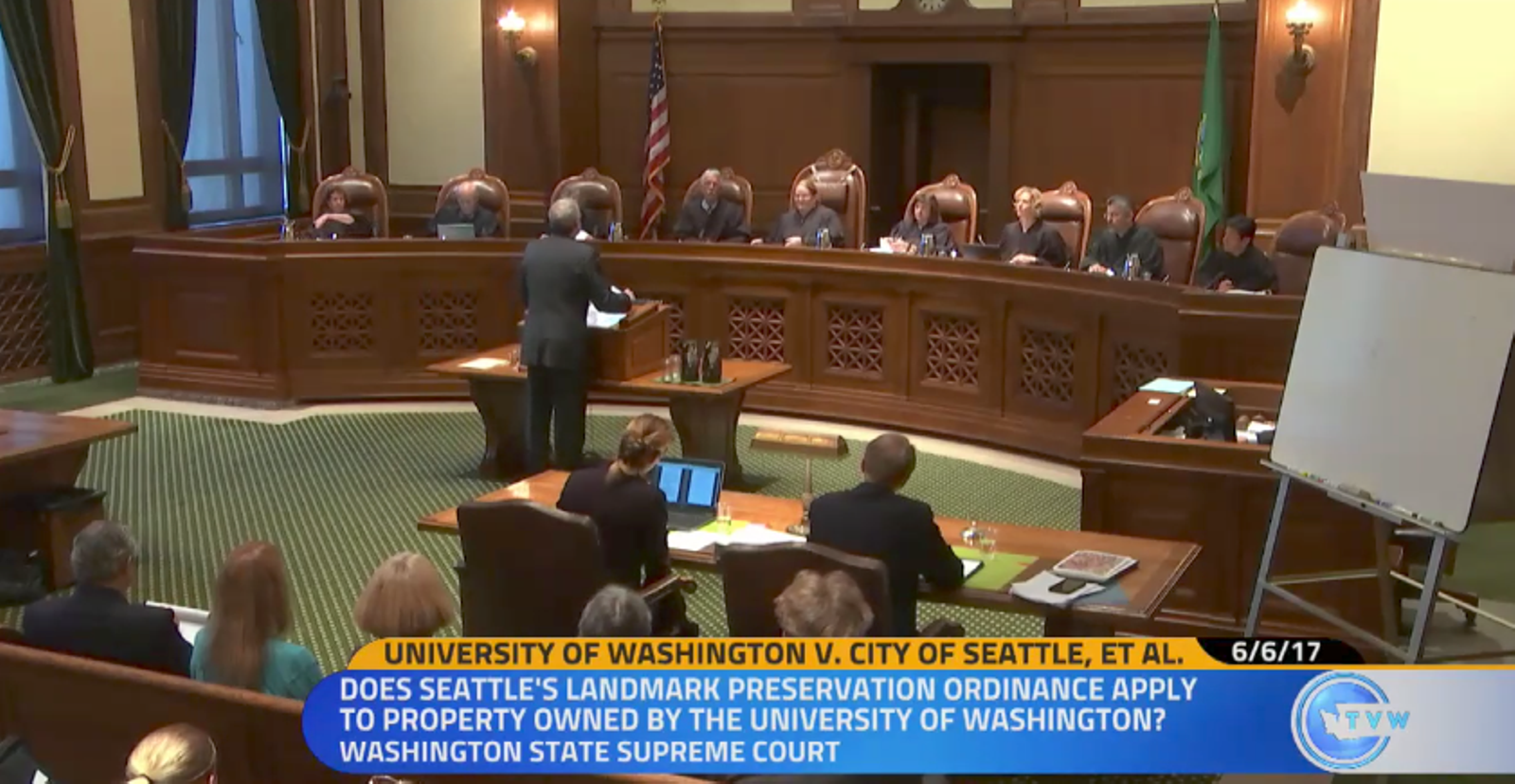

In the Fall of 2014, the University unveiled plans to construct a new Computer Science and Engineering II Building on the site, which would require demolition of the Nuclear Reactor Building. Because of the building’s significance and the seriousness of the threat, the Nuclear Reactor Building was re-listed on the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation’s list of 2015 Most Endangered Places. In late 2015, Docomomo WEWA submitted a landmark nomination to the City of Seattle. The University of Washington, claiming it was not subject to they City’s Landmark Preservation Ordinance because it was a state agency, filed a lawsuit against the City of Seattle and also named Docomomo WEWA in the suit. The Washington Trust and Historic Seattle also joined the lawsuit as intervenors.

Preservation advocates lost the first round of legal proceedings in King County Superior Court. On April 14, 2016, King County Superior Court Judge Suzanne Parisien issued an order granting the University of Washington its motion for summary judgment in its lawsuit against defendants City of Seattle and Docomomo WEWA, and intervenors Historic Seattle and the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation. Although advocates continued to try to slow the demolition process, UW moved forward and the Nuclear Reactor Building was demolished on July 19, 2016. Despite the loss of the building, the fight to protect other historic buildings on state-owned university campuses continued on.

The City of Seattle appealed the King County Superior Court decision and the case was elevated to the Washington State Supreme Court. The almost decade-long fight to protect historic resources at the University of Washington has culminated in a State Supreme Court ruling in favor of preservation advocates in the case—University of Washington vs. City of Seattle, Docomomo WEWA, Historic Seattle, and the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation. On July 20, 2017 the State Supreme Court of Washington issued its opinion—a precedent-setting unanimous decision—holding that the Seattle Landmarks Preservation Ordinance applies to property owned by the University of Washington. The Court ruled that the University of Washington is a state agency that must comply with local development regulations adopted pursuant to the Growth Management Act.

The Supreme Court win won’t bring back the Nuclear Reactor Building (may it rest in peace), but it can help save other properties owned by UW in the future and may serve as an important precedent for future cases regarding historic properties across the state. Universities not only manage their campuses, but they also own properties in downtowns areas in the hearts of Washington communities small and large.

Even though the building has been lost, we are honored to accept, along with our advocacy partners Docomomo WEWA and Historic Seattle, a Docomomo US Modernism Award of Excellence in Advocacy.