The Maritime Underground Railroad of Puget Sound

By Lorraine McConaghy, Historian.

Image: Although there are no known photographs of Charles Mitchell, award-winning illustrator R. Gregory Christie created this image of the young boy on the verge of a life-changing decision.

In September 1860, a Black teenager ran away from slavery in Olympia, Washington Territory. An African-Canadian network helped him flee to Victoria—but Charles Mitchell’s “underground railroad” was a steamer on Puget Sound.

The boy had been born into slavery on a Maryland plantation, son of a Black house slave and a white Chesapeake Bay oyster fisherman. Charles Mitchell was born in 1847 and named for his father. His mother—whose name we do not know—died in the cholera epidemic of 1850 and on her deathbed begged her mistress, Rebecca Gibson, to “take good care of my Charlie.”

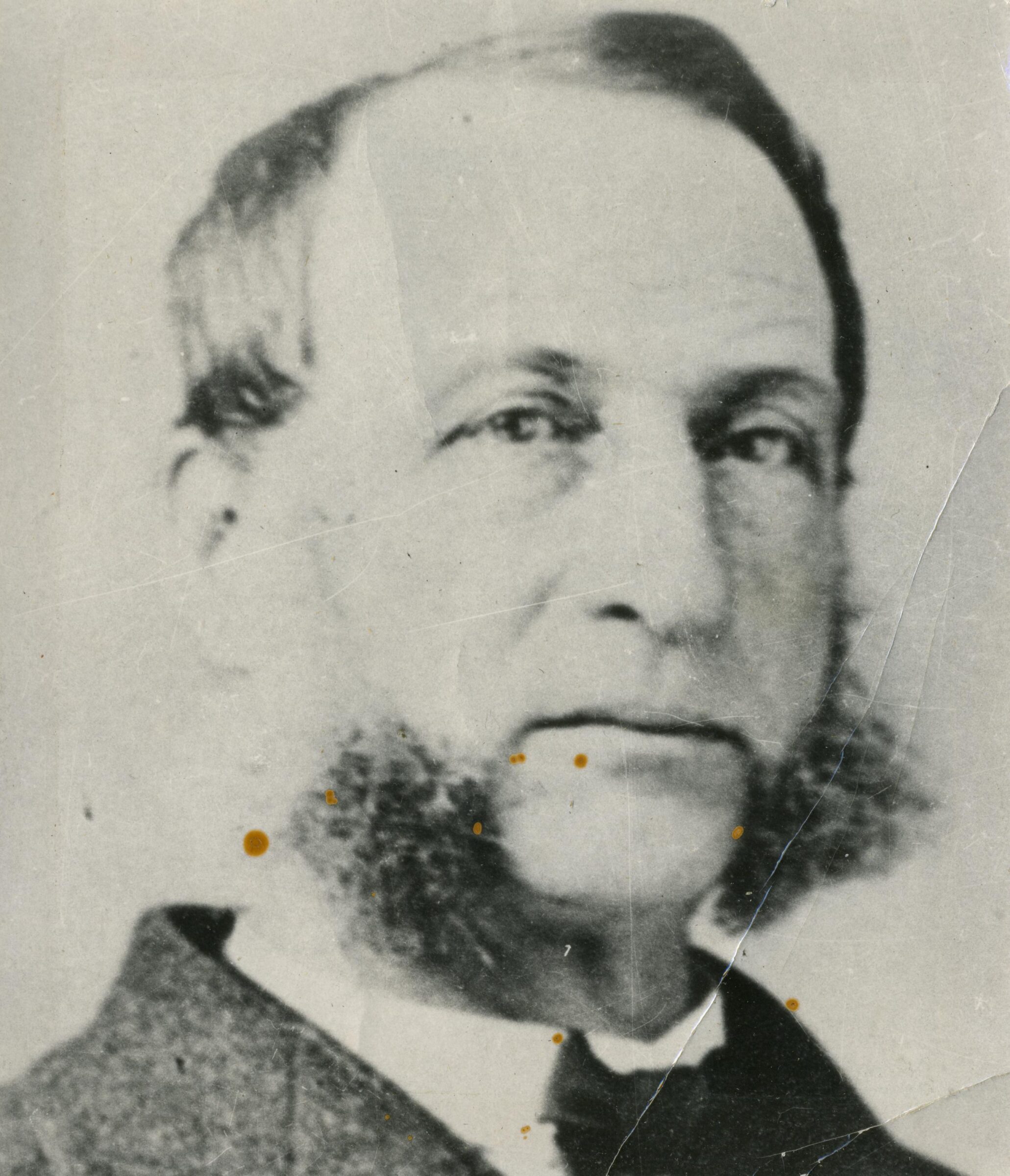

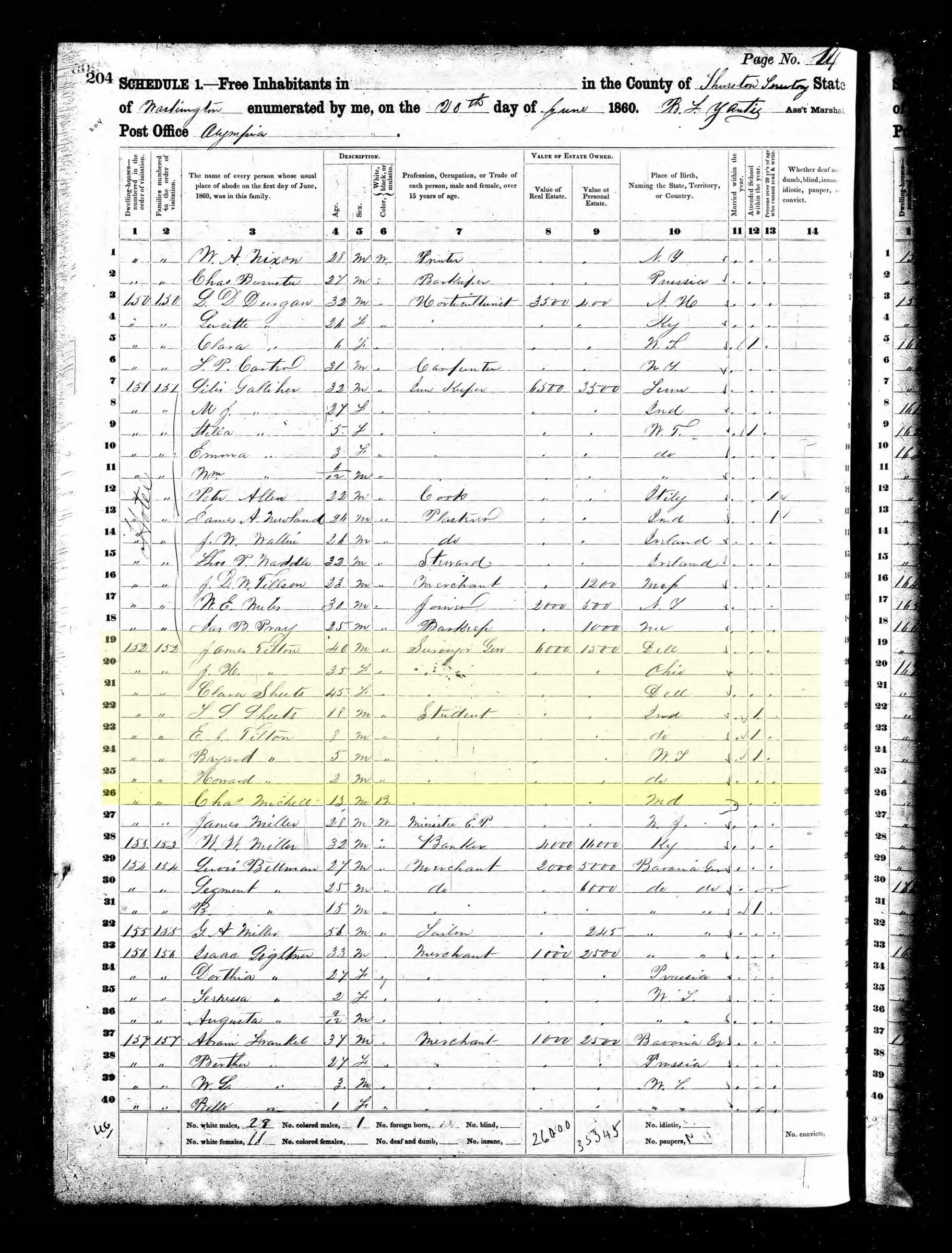

Mistress Gibson gave Charles to her cousin James Tilton—the boy was considered to be no more than a piece of property. Tilton had been appointed Surveyor General of Washington Territory, a patronage reward for his political efforts to get Franklin Pierce and then James Buchanan elected to the U.S. presidency. Tilton brought his household west, including Charles Mitchell.

The Tilton family arrived in 1855 and settled in Olympia. After the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857, chattel slavery was legalized in the territories, which meant that Charles Mitchell was legally owned at the Olympia house.

The years following Tilton’s appointment were dramatic ones in the new territory, as hasty, exploitive treaties were “negotiated” with Tribes. Afterward, many Native people resisted the treaty terms and fought back in the Treaty War of 1855-1856. Tilton took a major military role in that conflict, as well as in the post-treaty surveys of territorial land for settlement.

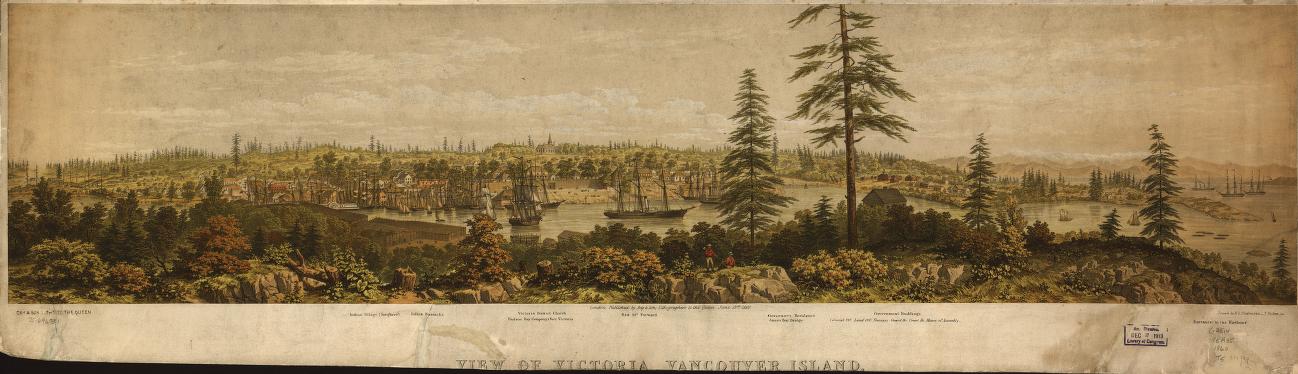

An African-Canadian man, William Jerome, spent some time in Olympia and noticed Charles Mitchell in the marketplace, the shops, the street. While Charles was not the only person of color in western Washington Territory, he was the only enslaved person we know of. Jerome returned to Victoria and spoke with members of the Black community there. In 1860, Victoria was about 20% Black, following a mass migration of families of color from San Francisco, escaping California’s systemic racism. Victoria’s community included Black men and women who had participated in the underground railroad back East and who had helped many fugitive slaves escape to Canada.

With the help of that community, three Black men—James Allen, William Davis, and William Jerome—devised a plan to approach Charles Mitchell and encourage his escape to the freedom of Victoria on a maritime underground railroad. James Allen was the cook on board the sidewheel steamer Eliza Anderson, which had the international mail run between Olympia and Victoria, pausing at flagged stops along the way. Two of the men approached Charles Mitchell in secret in Olympia and persuaded him to escape.

On September 24, 1860, Charles stole out of the Tilton house at dawn and ran down the hill to Percival Landing where the Eliza Anderson was getting up steam. Cook Allen was waiting for him and waved him on board, hustling him down to the galley and hiding him there. Davis was a passenger on board the steamer, keeping an eye on Charles Mitchell.

The Eliza Anderson steamed north and stopped in Seattle so that a U.S. Army squad could search for deserters from Fort Steilacoom. They found no deserters, but they did find Charles Mitchell hidden in the galley. Hauled before the steamer’s captain, John Fleming, Mitchell was recognized as James Tilton’s property. The captain decided to return Mitchell to Tilton in Olympia and that in the meantime Mitchell would work for his keep, shoveling coal to fuel the steam boiler.

As the Anderson steamed toward Victoria, Captain Fleming considered his position. Fleming decided to fire James Allen and put him off the vessel in Victoria. He had also likely guessed that passenger Davis was a member of the African-Canadian conspiracy “to set a bond boy free.”

At the Victoria waterfront, a large crowd awaited the Anderson’s docking. They jostled and murmured, “Where is the boy?!” Fleming announced from the steamer’s deck that he refused to release Charles Mitchell, who was locked up on board, and that he intended to return the boy to his master in Olympia.

The three African-Canadian conspirators rushed to the Victoria law office of barrister Henry Crease. There, they filed affidavits declaring their knowledge of Mitchell and his efforts to escape slavery in Olympia. Crease hastened to request a writ of habeas corpus from the civil authorities. The writ, delivered by Victoria’s sheriff and his burly deputy—and supported by an increasingly angry crowd—convinced Captain Fleming to reluctantly release Charles Mitchell to custody on shore.

After the boy’s night in jail, Crease represented him before the Supreme Court of Civil Justice, and Mitchell was freed. “It was,” editorialized the Victoria Colonist, “a righteous decision.” Charles Mitchell was free to grow up in the welcoming Black community of Victoria.

Owner James Tilton, Captain John Fleming, and Washington Territorial acting governor Henry McGill all wrote heated letters to protest Charles’ “seizure” as a violation of international marine law. Little came of their protests, though Mitchell’s escape was covered by newspapers up and down the West Coast. After his schooling in Victoria, Charles Mitchell joined many Black Victorians as they returned to San Francisco after the Civil War’s conclusion.

Charles Mitchell is the only passenger we know of on Washington Territory’s underground railroad, created and staffed entirely by African-Canadian men. This extraordinary maritime story became a flashpoint for discussion of race and slavery in the Territory, as newspapers in Port Townsend and Olympia decried “the worthless free negroes from Victoria” who had alienated Mitchell from his master. But the Steilacoom Puget Sound Herald anxiously pointed out that a western maritime underground railroad to “the British Possessions on this Coast” was as likely as the well-established routes back East. In the future, more research may reveal other voyagers on the Puget Sound underground railroad.

Want to learn more about the Charles Mitchell story? Check out the book Free Boy by Lorraine McConaghy and Judy Bentley.