The Spaces Between the Buildings: Latine Claims on Space, Place, and Preservation in the Pacific Northwest

By Raymond W. Rast, Ph.D., Associate Professor & Department Chair of History, Gonzaga University; Board Member, Latinos in Heritage Conservation; Board Member, Washington Trust for Historic Preservation

Shared with permission from The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Spring/Summer 2023

In November 2019 the New York Times published a feature story, “The Divide in Yakima Is the Divide in America.” The story focused on the largest city in Washington’s Yakima Valley, the growth of the city’s Latine population, and the political changes that have come as a result.1 Much of the story revolved around then 26-year-old Dulce Gutiérrez. The daughter of Mexican immigrants, Gutiérrez was born and raised in East Yakima and graduated from the University of Washington. In 2015, after a federal judge ordered a switch from at-large voting to district-based voting for Yakima’s seven-member city council, Gutiérrez won a seat with 85 percent of the vote.2

Gutiérrez joined two other newly elected members as the first Latinas ever to serve on the Yakima City Council. They took office in 2016, the same year that Yakima’s mostly older, white voters cast their votes overwhelmingly for the presidential candidate Donald Trump. These facts are not unrelated. Latine-serving businesses had proliferated in Yakima, Latine families outnumbered white families in the public schools, and Latine taxpayers were demanding better city services. For many of Yakima’s older white residents, demographic changes and their consequences were coming “too fast.”3 According to the local talk radio host Dave Ettl, the people “pushing” these changes—like the people Trump had castigated during his campaign—were doing so “too far, too left, too soon.”4

Six months before the New York Times published this story, the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation, in partnership with a consulting firm, completed a two-part Latine heritage study funded by the Washington Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation and the National Park Service. One part of the study focused on the Seattle area, but the other part documented Latine population growth in the Yakima Valley and the consequent effects on the valley’s agricultural economy, cultural diversity, labor rights battles, and built environment dating back to the 1940s.5 In other words, the changes that people like Ettl thought were coming “too fast” had been coming for nearly 80 years. In the Pacific Northwest as a whole, these changes had been underway for even longer.6

To be sure, the region’s Latine population has grown significantly in recent decades, and Latines have attained a level of visibility in the Pacific Northwest on par with that in other regions beyond the Southwest. As the scholars Douglas Massey and Chiara Capoferro have noted, prior to the 1930s, Mexican immigrants in particular were concentrated in the Southwest, with 86 percent going to Texas, California, and Arizona. Although Illinois soon surpassed Arizona, this level of concentration continued into the 1980s. The trend then shifted in the 1990s, when only 49 percent of Mexican immigrants settled in California, Texas, and Illinois, and most of the rest dispersed to other “new destinations” in the South, Midwest, and Pacific Northwest.7

The shift to new destinations has helped drive the number of Latines in the Pacific Northwest to around 1.8 million, constituting 13 percent of the total population. This figure remains lower than the national share of 18 percent, but the rate of growth is significant. Between 2000 and 2010, as the region’s total population grew by 15 percent, its Latine population grew by 72 percent. The rate of Latine growth since 2010 has fallen to 27 percent, but that is still more than twice that of the region as a whole. Of the Northwest’s 1.8 million Latines, roughly 1 million live in Washington, more than half a million live in Oregon, and the remainder live in Idaho.8 Latines live in agricultural areas such as the Willamette Valley and the Columbia Basin; in smaller cities and towns such as Pasco, Washington, and Woodburn, Oregon; and in the region’s metropolitan areas.

In all these places, Latines have shaped economies, classrooms, and communities. As the Washington Trust’s heritage study makes clear, Latines have also shaped the built environment. Even with a focus on just the pre-1970 Yakima Valley and the pre-1990 Seattle area, the study identified two potential historic districts, 43 properties eligible for individual listing on the National Register of Historic Places, and 15 additional properties that would be eligible if they had retained more of their physical integrity. Property types included meeting halls, theaters, churches, schools, organization offices, radio stations, health clinics, houses, and public parks.9

To see this impact on the region’s built environment more broadly—to see places Latines have made in the Pacific Northwest but also spaces Latines have occupied, activated, and claimed—we have to know where and how to look. That means we have to draw on the methodologies of scholars who study space and place, the built environment, and cultural landscapes. It also means we have to draw on the methodologies of those who study history and engage in historic preservation, emulating the work of those who contributed to the Washington Trust’s heritage study through their use of oral history interviews, archival documents, photographs, and field surveys. Ultimately, we have to combine these methodologies. We have to analyze space and place and the ways in which both have changed over time.

The preceding paragraphs originated in a paper I presented at the annual conference of the Society of Architectural Historians in 2020.10 Joining a session titled Sites Unseen: Other Cultural Landscapes of the Pacific Northwest and speaking mostly to architectural historians and historic preservationists, I argued that, while Latine “placemaking” has received more attention from scholars and practitioners in recent years, Latine occupation and activation of spaces also have contributed to the Latinization of landscapes, especially in the Pacific Northwest.11 In this essay, I present more of my research and put a finer point on my argument. Surveying Latine claims on place and space in the Pacific Northwest during the 20th century, I argue that both types of claims were assertions of belonging and of a right to belong. Latine claims on place and space thus have shaped the region, its people, and its history.

Before turning to this argument more fully, I want to take the opportunity afforded by this special issue to explain why I present these kinds of arguments to these kinds of audiences. I want to explain why, for more than 20 years, I have engaged with audiences that include architectural historians and historic preservationists as well as geographers, urban planners, and other interdisciplinary scholars and practitioners. As a preservationist myself, I have learned a lot from the work of these colleagues. As a historian, however, I have been compelled not only to critique some of the ways in which some of these colleagues approach our collective work but also to make the case for alternative approaches.

My own work in historic preservation has been motivated, in part, by my mother’s stories about the house and neighborhood in which she grew up in the 1950s. My maternal grandparents emigrated separately from Mexico to the U.S. and eventually settled in Kansas City, where they met, married, and bought a modest house in the city’s Westside barrio. My grandfather died in 1954, and the house was one of hundreds demolished a decade later so that another freeway could be built through the city.12 For my mother and her siblings, losing that house meant losing a substantial material connection to their father and their childhood memories. It deprived their own children and grandchildren of that connection as well. I believe historic preservation, at its best, can prevent such losses.

Most of my preservation work has focused on Latine history and heritage. Working with the National Park Service, I helped produce the Cesar Chavez Special Resource Study (2012) and American Latinos and the Making of the United States: A Theme Study (2013).13 Working with Latine stakeholders, I have nominated properties for National Historic Landmark designation and listing on the National Register of Historic Places. Since 2014 I have served as a cofounder and now board member for Latinos in Heritage Conservation, the nation’s leading advocacy organization for the preservation of Latine places, stories, and cultural heritage. I also serve on the board for the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation and on the Spokane Historic Landmarks Commission.

In the course of doing this work, I have learned much from other scholars. I have learned, for example, that when people act within space in order to strengthen or challenge social relations, they might develop a sense of identity, a sense of belonging, and a sense of place. As Paul Groth explains, cultural landscape scholars in particular show us how people use “everyday space” to “establish their identity, articulate their social relations, and derive cultural meaning.”14 Such actions turn undifferentiated space into known, valued, and memory-filled place. Drawing on the work of the geographer Yi-Fu Tuan, Theresa Delgadillo elaborates, noting that space is devoid of attachments, but place is “a site of belonging, of affective attachments and memories and interrelationship.” Positionality also matters. Th us “what is ‘space’ to one group may well be ‘place’ to another, and vice versa.”15

Many scholars now study cultural landscapes through the lenses of race and ethnicity, often emphasizing how the production of racialized landscapes has long been a means of protecting white privilege and oppressing people of color. Richard Schein thus argues that cultural landscapes “are not innocent.” They are material artifacts, but that means they are “constitutive of the processes that created them.”16 Racialized landscapes include not only “chocolate cities and vanilla suburbs” produced by redlining and racial covenants but also older Chinatowns, Japantowns, Little Manilas, and Mexican barrios.17 Historical scholarship on the segregation of ethnic Mexicans into barrios actually anticipated broader interest in racialized landscapes.18 Albert Camarillo called the process “barrioization,” and it meant more than just the geographical concentration of a community—it meant the loss of collective wealth, social status, and political power.19

Latine scholars and practitioners seeking alternatives to the concept of barrioization have built on the work of the urban planner James Rojas in order to advance the concept of barriology. Rojas has long stressed that, when studying Latine claims on space and place, we must study not only the built environment but also the “enacted environment.”20 Focusing on East Los Angeles, Rojas has documented the ways in which ethnic Mexicans create cultural landscapes through their everyday use of streets and sidewalks, selection of vibrant paint colors for homes and murals, conversion of front yards into personalized spaces, use of “props” such as push carts, and even their use of food and music.21 Enacted environments are not planned. In many ways they are not even built.22 Instead they are “made up of individual actions that are ephemeral but nevertheless part of a persistent process.”23 Such actions have meaning—they reflect “the struggles, triumphs, and everyday habits of working-class Latinos.” Thus “the front yards of East Los Angeles are not anonymous spaces but personal vignettes of owners’ lives.”24

Raúl Homero Villa wedded Rojas’s ideas to the concept of barriology, which captures the “expressive practices” of barrio life—including ephemeral everyday actions—that “reveal multiple possibilities for re-creating and reimagining dominant urban space as community-enabling place.”25 Building on Villa’s work, the geographer Lawrence Herzog offers an explanation of barriology that begins to illuminate my own work in historic preservation and my argument in this essay. Surveying Latine efforts to remake cultural landscapes in San Diego, Herzog emphasizes the importance of buildings but also public spaces and the social interactions associated with them. “It would be a mistake to restrict discussion of Latino…landscapes to the buildings alone,” he notes, because “the spaces between the buildings are often equally or more important to the overall cultural landscape.”26 By occupying, activating, and thereby claiming these spaces, Latines move “from a condition of being barrioized” to one in which they feel “a sense of belonging, a sense of place, a barriology.”27

In my work and in this essay, I adopt the concept of “the spaces between the buildings” as a metaphor for my professional interests because, as a historian and as an advocate for Latine heritage conservation, I care about buildings—but I care about the spaces within them, around them, and between them even more. And this has been the basis for my critique of historic preservation and my calls for alternative approaches. As a historian, I am interested primarily in people and their actions, interactions, values, stories, struggles, and the places and spaces that reflect their sense of belonging. Most of these things are indeed more ephemeral than buildings—they are less visible, less enduring—but that does not make them any less significant or less worthy of documentation and preservation.28

I am interested in these things as a preservationist, too, and this is why I occupy an uneasy terrain between the fields of history and preservation. Whereas historians value the ephemeral and the intangible, many preservationists question how such things can be “preserved.” Historians likewise are interested in change over time, but many preservationists are drawn to the field because they value stasis. For them, preservation means preventing change over time. Many preservationists thus defend preservation standards that give physical integrity the same weight as historical significance. For them, the less a building has changed—the more it has retained its integrity—the more it merits preservation protections.29 Historians, of course, find value in well-preserved artifacts, but we also recognize that all artifacts, including buildings, change over time. As Stewart Brand has noted, the word building itself captures the reality. It means both “the action of the verb build” and “that which is built.” It is both verb and noun, both action and result. Even “preserved” buildings are never entirely static—they are always undergoing change.30

As a historian and as a preservationist, I also follow the art historian Jules David Prown in recognizing a divergence among those who are drawn to material culture. Some of them are interested primarily in material, and some of them are interested primarily in culture. The former, Prown argues, are inclined to gather and organize information. They concentrate on the characteristics of artifacts “consciously put there by the makers.”31 The latter likewise are interested in “the facts” of an artifact, but they are more interested in understanding and explaining why those facts matter—what they mean and what they tell us about whoever produced them.32 They believe the facts must be connected to broader stories and larger contexts. In short, they must be interpreted.

Nearly a century ago, the first chief historian of the National Park Service, Verne Chatelain, emphasized the latter perspective. In making the case for historic preservation, he argued that cultural landscapes could offer as much material for studying, teaching, and learning history as any collection of documents in an archive. “There is no more effective way of teaching history,” he insisted, than to take someone to a site at which some meaningful event occurred and there convey “an understanding and feeling of that event through the medium of contact with the site itself, and the story that goes along with it.”33 In much of my work as a historian and a preservationist, I try to reconnect places and spaces to the stories of Latine history and heritage that go along with them. In the rest of this essay, I suggest what it looks like to do so with a focus on the Pacific Northwest during the 20th century.

Latines claimed spaces and made places in the Pacific Northwest throughout the 20th century. Arriving mostly as sojourners during the early decades of the century, thousands of working-class Mexican immigrants faced hardship and discrimination but nevertheless occupied, activated, and thus claimed spaces in some of the region’s fields and orchards, labor camps, and religious and recreational buildings in nearby towns. During the closing decades of the century, hundreds of thousands of Latines of Mexican, Central American, South American, and Caribbean descent were born in the Pacific Northwest or continued to come to it. Characterized by cultural diversity but also strong values, family ties, and faith traditions, they made visible and enduring places throughout the region: homes, small businesses, community centers, health clinics, cultural centers, even farms and orchards of their own. From the 1910s through the 1990s and beyond, Latines ultimately did both. Their efforts to claim spaces may have been more ephemeral than their efforts to make places, but both types of eff orts were assertions of belonging and of a right to belong in the Pacific Northwest.

Most Latines who came to the Pacific Northwest from the 1910s through the 1950s were ethnic Mexicans.34 The earliest arrivals during the 1910s and 1920s had been recruited by agricultural employers. A much larger influx came during the 1940s under the auspices of the Bracero Program. Employers then recruited ethnic Mexican migrant workers from Texas who came to the region seasonally but began to stay year-round. Speaking about men and, increasingly, women and children such as these, the historian Rodolfo Acuña has argued that “when you are [a migrant worker]…you are very vulnerable…. There is very little integration of other ideas…when you’re constantly moving. You never form a sense of place.”35 Acuña’s assertion might be overstated, but he was not wrong about the difficulties Latines faced throughout these decades, especially in the agricultural areas of the Pacific Northwest. Despite such challenges, Latines claimed spaces in fields and orchards, labor camps, movie theaters, churches, and dance halls. Some of them even began to make places, opening and patronizing the region’s first Latine-owned businesses.

The U.S. instituted restrictive entry requirements for immigrants in 1917. World War I had already tightened the labor market, so the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company and other employers in the West secured specific exemptions for the Mexican immigrants they recruited. Thus by the 1920s, hundreds of Mexican immigrants worked in sugar beets in Idaho’s Snake River Valley, and hundreds more were moving into the beet fields and factories of Oregon and Washington, into other crops, and into other industries.36 Census data is incomplete, but it suggests that the number of Mexicans living in the Pacific Northwest quadrupled, reaching 2,000 during the 1910s.37 The region’s Mexican population grew more slowly during the 1920s and then declined to around 1,000 during the 1930s.38 Given the growth of anti-immigrant hostilities during the 1920s and the economic conditions of the 1930s, this reversal is not surprising.39

World War II brought the first significant influx of Latines to the Pacific Northwest. Some of them came because of military service. Stationed at bases such as Fort Lewis in Tacoma, they explored the region and later decided to return. Manuel Barrón, for example, was born in Texas and enlisted in the army in 1942. He spent time at Fort Lawton, liked what he saw of Seattle, and landed a factory job in Ballard in 1945.40 Wartime labor shortages brought even more Mexican workers. Responding to the loss of agricultural workers to military service and manufacturing, the U.S. and Mexico created the Bracero Program in 1942. Essentially a guest-worker program, it allowed U.S. employers to hire Mexican men for seasonal agricultural employment. Employers were required to provide fair wages, adequate food and housing, and protection from discrimination, but such requirements often went unenforced. Over the next five years, employers brought nearly 220,000 braceros to the U.S., including more than 40,000 to the Pacific Northwest.41

The Bracero Program continued until 1964, but the elimination of transportation subsidies after 1947 made it less tenable for regional employers. The historian Erasmo Gamboa also notes that regional employers faced growing challenges from braceros who protested low wages, inadequate food and housing, and discrimination. Concluding that other ethnic Mexican workers might be controlled or replaced more easily, employers began to recruit Tejanos (ethnic Mexicans from Texas).42 As the historian Errol Jones concludes, employers came to value Tejano workers because they worked hard for low pay and “vanished when the work was done.”43 Tejanos, of course, had their own reasons for accepting offers of seasonal work in the Pacific Northwest, including promises of better pay. By the mid-1950s, roughly 80,000 migrant workers spent an average of six months in the region every year. Nearly 80 percent of them still considered Texas to be their home.44

In many ways, the experiences of the Castañeda family represent those of ethnic Mexican migrant workers who came to the Pacific Northwest from the 1910s through the 1950s. A labor contractor in Crystal City, Texas, recruited José Castañeda to work in the shipyards of Vancouver, Washington, in 1944. His family stayed behind, but in 1946, his wife, Irene, decided they should join him. After a harrowing trip in the back of a crowded truck, Irene and her children reunited with José in the Yakima Valley and soon started working at the Golding Hop Farm near Toppenish.45 Their daughter, the historian Antonia Castañeda, has explained that their lives in the years that followed were largely defined by their labor in the fields and orchards in which they cultivated “cotton, spinach, potato, beet, tomato, melon, hop, cucumber, lettuce, beans, asparagus, berries, apple, grape, peach, plum, lemon, and cherry.”46 In these spaces, from dawn to dusk, their bodies worked individually and in unison—a “sea of humanity moving up and down the rows chopping, hoeing, weeding, cutting, topping, twining, tying, thinning, pruning, picking, harvesting.”47 Such actions shaped the region’s landscapes, generated wealth, and fed the nation, but these actions also were ephemeral. For most people, they were invisible.

After dusk, migrant workers’ lives and domestic labors continued in the spaces of labor camps. While working at the Golding Hop Farm, the Castañedas lived in a company-owned camp, with housing that Irene described as “a row of doorless shacks that were falling apart.”48 Outhouses and washrooms were communal, and cooking was makeshift.49 Tens of thousands of ethnic Mexican migrant workers confronted similar housing conditions. Braceros often lived in tent camps hastily constructed on county fairgrounds.50 Other workers found better housing in government-run facilities such as the Crewport Farm Labor Camp near Granger. Constructed in 1941, it offered 41 small houses, 200 cabins, and 142 tents on concrete slabs. It also included daycare and recreational buildings, a post office, and a small grocery store.51

The conditions of all these camps varied, but they generally deteriorated as the decades passed. Another common characteristic was their isolation. The geographer Lise Nelson has argued that the 20th-century labor camp, by design, “spatially contain[ed] farmworkers, making them invisible, and function[ed] as a mechanism of control by employers.”52 Yet ethnic Mexicans found ways to make the camps more livable—they acted in ways that were ephemeral but nonetheless meaningful, and thereby made claims on these spaces. Erasmo Gamboa notes the ways in which braceros, for example, decorated their tents with “pictures of loved ones, tokens of remembrance, or knickknacks purchased locally.”53 Other workers enjoyed baseball games and festive gatherings to celebrate first communions, confirmations, and quinceañeras, all of which drew families from other camps and nearby towns.54

Ethnic Mexicans living in labor camps during these decades did not visit other camps or nearby towns without some difficulty. Employers near Medford apparently required braceros to seek permission before visiting the town for entertainment or shopping.55 Employers elsewhere sometimes helped with transportation, but otherwise the men had to arrange it on their own. Once in town, braceros sought out clothing stores as well as beer parlors, pool halls, and dance halls. They often faced harassment and discrimination, but many of them were defiant, and, when opportunities arose, they often flirted, drank, and danced with local women.56 The historian Mario Sifuentez argues that, for braceros, these were “small acts of reclaiming space and making themselves visible.”57

Tejano families often went into town to shop and perhaps go to a soda fountain or movie theater. Starting in the early 1950s, Leobardo Ramírez screened Mexican films on Sunday afternoons at the Avalon Theater in Sunnyside.58 Belen Pardo, a Tejana who lived at Crewport from 1945 to 1953, recalled visits to the Granger Theater, where “they played lots of movies in Spanish.”59 Pardo’s family, like many others, also went into town to participate in the life of local faith communities. The Catholic Church created the Diocese of Yakima in 1951 and provided the Yakima Valley with its first Spanish-speaking priest (who confirmed 513 ethnic Mexican children in 1952).60 This priest and others in the region ministered in the camps, but increasingly they did so from churches in town.61 Although religious services came with pressures to assimilate, many Tejano families wanted to strengthen their ties to their faith and each other.62 As the historian Josué Estrada suggests, Tejanas such as Pardo “claimed…public space” through this engagement.63

Dances and other community events held in repurposed venues provided some of the most enjoyable opportunities for ethnic Mexicans to claim spaces during these decades. In the 1950s, Tejano families in the Yakima Valley, for example, rented meeting halls such as the Wanita Grange Hall near Sunnyside and used them for dances, weddings, and other celebrations that featured accordion-driven music known as conjunto.64 Antonia Castañeda has articulated the connection—and the distinction—between how bodies moved to the rhythm of work in the fields and then to the rhythm of conjunto in the dance venues. What she learned in the fields about her body’s capabilities “became the basis for moving through space…in the fields, in the camp where we lived, but also on the dance floor.”65 When she danced, she did so with a “freedom of movement and ease” that came from hard-won strength and endurance.66 But dancing also was “about moving out of spaces of oppression and exploitation.”67 The dances were meaningful because they provided “spaces…in which we could be who we were and move in the way that…mattered to us.”68

Like so many Latine claims on spaces in the Pacific Northwest, movements on dance floors were ephemeral, and Castañeda is careful not to overstate the visibility or durability of such claims. She emphasizes that ethnic Mexicans were “made to feel that we didn’t belong.”69 Yet here we also can begin to see how buildings—and the spaces withinthem—accrued meaning and became places. As touring conjunto bands became popular, organizers sought larger and more permanent venues. An old meeting hall in Toppenish thus became La Puerta Negra. A former roller-skating rink in Sunnyside became El Baile Grande.70 Castañeda notes that dances were held in dilapidated buildings like “the roller rink [where]…the cement was all cracked,” and she concedes that this venue “would have been considered a shabby place.” Yet she emphasizes that, “for us, it was as elegant as any elegant ballroom. It could be, because it was ours and because we were dancing.”71

The region’s first Latine-serving businesses accrued similar meaning. Tony Rodriguez, who had settled in Idaho in 1941 and returned after serving in World War II, opened a barbershop in Nampa in 1949. Following his own wartime service, Manuel Barrón worked in Ballard (north of Seattle) until he moved to south Seattle and opened Barrón’s Barbershop in 1954. Both of these businesses became significant local hubs for ethnic Mexicans—places in which ephemeral but meaningful interactions occurred.72 Latine entrepreneurs also opened tortillerías and restaurants during these years, including González Tortillería in Ontario (Oregon), El Charro in Nampa (also opened by Tony Rodriguez), and Espinoza’s in Seattle. The most enduring Latine-serving restaurant was El Ranchito, which T. W. Clark and Elsie Clark opened in Zillah (Washington) in 1951. The Clarks were not Latine, but they sold fresh tortillas and other food in labor camps and gained a loyal following. Their restaurant’s central location, welcoming atmosphere, and authentic recipes helped it become a significant regional hub for ethnic Mexicans.73

El Ranchito and other restaurants took on some of the significance the historian Natalia Molina associates with the Mexican restaurant her grandmother opened in Los Angeles in 1951. Even in California, Latines in the 1950s often were invisible, often by choice—invisibility reduced the odds of harassment and discrimination. In restaurants like El Ranchito, however, customers could speak their own language, eat their own food, and just be themselves. They could “become visible, speak out, and claim space…. They could belong.”74 Geography made restaurants in the Pacific Northwest even more meaningful. When Julian Ruiz moved to the Willamette Valley in 1951, the “most difficult thing was that Mexican foods were not found in the local grocery stores. This meant no fresh or canned chiles or other Mexican spices, pan dulce, chorizo, or tortillas,” all of which “were readily available…in south Texas.”75 Restaurants thus turned buildings into places where Latines could connect with the food and culture they missed. Restaurants provided the comforts of home. In doing so, they helped Latines think that the Pacific Northwest itself might become home.76

That possibility continued to grow through the 1950s and beyond. Tens of thousands of Tejanos divided their time between Texas and the Pacific Northwest, but every year more of them decided to stay in the Northwest year-round. Financial considerations were an important factor in the decision to settle. In good years, agricultural work was available from March through October. If work was available in Texas during the other four months, the move back would be worthwhile—but this was not a certainty. If it had not been a good year, savings would be lower and the stakes would be even higher.77 Family considerations also played an important role.78 Baldemar Diaz and his family, for example, began coming to the Yakima Valley in 1956. They returned to Texas every year, but concerns about the children’s well- being led them to settle in Washington in 1959. Before that point the children “struggled because when we went back to Texas, they were [in school] there for about a month and half…. [With] all the relocating, they lost a lot of school. And after we settled, they began to do good.”79 Growing up in the Pacific Northwest, this next generation of Latines would face persistent challenges. They also would claim spaces, make new places, and thereby assert their right to belong.

From the 1960s through the 1980s, the Latine population in the Pacific Northwest continued to grow, diversify, and spread. The numbers of Central and South American immigrants increased, but the numbers of Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants increased even more. Settled families, migrants, and immigrants alike claimed spaces in fields, orchards, forests, and labor camps, but many of them now bought houses and turned them into homes. They claimed spaces in towns and cities, and increasingly these claims were multigenerational. They also opened more restaurants and other small businesses. Inspired by the farm-worker movement and the Chicano movement, they turned many of these spaces and places into loci for organizing and activism. Ultimately, Latines continued to assert the right to belong in the Pacific Northwest—to work, raise their children, maintain their culture and values, and claim the spaces and make the places necessary to do all these things.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the growth, diversity, and diffusion of the region’s Latine population reflected the actions of Tejano families like that of Baldemar Diaz. They settled in the region, encouraged family members to join them, and had more children of their own. As the region’s economy continued to grow, demand for agricultural labor also attracted new waves of documented and undocumented immigrants from throughout Latin America. The region’s Latine population thus surpassed 143,000 during the 1960s and reached 249,000 by the late 1970s.80 This population remained predominantly ethnic Mexican (69 percent), but 27 percent were Central or South American, and 4 percent were Puerto Rican or Cuban.81 This population also spread geographically, moving into developing agricultural areas such as the Columbia Basin, gravitating toward urban areas, and, for many, continuing to migrate within the region seasonally.82

These trends persisted during the 1980s as the region’s Latine population surpassed 380,000.83 Civil wars led to an influx of Nicaraguan, Salvadorean, and Guatemalan immigrants, but economic turmoil brought an even greater number of Mexican immigrants, and the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 encouraged more of the latter to stay.84 Thus by 1990 the share of ethnic Mexicans in the region’s Latine population climbed to 78 percent.85 The diffusion of the Latine population also continued, partly because changes in agricultural production pulled Latine workers into new areas. Investments in reforestation, for example, led to the hiring of thousands of Mexican immigrants in the Rogue Valley.86 Likewise, farmers in the Walla Walla Basin and Skagit Valley invested more in specialty crops such as apples and berries that promised higher profits but also required more labor for harvesting and packing, and they turned to Latine workers as well.87 Latines who moved into service industries found work and made lives in the region’s cities and towns.88

Like other Latines during these decades, Rafael Pacheco and his family claimed spaces in the fields, orchards, and labor camps of the Pacific Northwest. The family settled in the Yakima Valley in 1970 but still migrated within the region. In April and May the family picked asparagus and trained hop vines near Sunnyside, moved around in June and July to harvest pears, peaches, potatoes, and berries, then returned to the Yakima Valley to harvest hops and grapes until November. Rafael pruned grape vines in December and January.89 The family found housing at the former Crewport Farm Labor Camp, which was privatized in 1968. When they worked beyond the Yakima Valley, however, they preferred to camp on their own, because most labor camps continued to lack adequate heating, toilets, cooking appliances, and refrigeration. Farmworker advocates called attention to these conditions, but owners ignored the problems or, as in the case of Crewport, found new owners.90 Migrant farmworkers had little recourse, so they tried to make the camps livable. A worker near Woodburn, for example, testified in 1985 that he lived in a camp in which the buildings were in disrepair. The owner “gives us a hammer and the nails and we look for lumber,” he explained. “We repair the leaks in the roof or we repair the floor to get them to be in living condition.”91

Conditions in the labor camps grew worse as the numbers of migrant workers increased. At the same time, growing numbers of Latines were leaving the camps or avoiding them altogether—they were buying houses. Within a year of the Pacheco family’s arrival in the region, an employer recognized their need for “a stable place” and offered to finance their purchase of a house near Sunnyside.92 Although countless other Latines bought houses during these decades, in some areas such purchases remained “newsworthy” well into the 1960s. Soon after Emilio and Hortencia Hernández settled in Forest Grove in 1962, Emilio landed a job as a foreman on a nearby farm. When they bought their first house in 1967, a television news crew arrived to gather their white neighbors’ reactions.93 If reporters had interviewed Emilio and Hortencia, they might have learned that, for Latines, buying a house signified sinking roots. Acquiring a house and making it a home—making it an enduring, memory-filled place—was an assertion of belonging and of a right to belong in the region.94

Wherever they lived, Latines continued to claim spaces in towns and cities, and now these claims became multigenerational. Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, who left Texas in the early 1960s to teach Spanish in Seattle, observed some of these claims when he first visited the Yakima Valley. Arriving in downtown Granger on a Saturday evening, he was struck by all of “the guys—the jovencitos” on the streets and sidewalks, freshly showered and wearing ironed shirts.95 They were “looking at the girls,” and the girls were looking back.96 “They were eyeing each other and there was this electricity.”97 He followed some of them “into a restaurantito, and they had Mexican food.”98 For him, “it was like a homecoming.”99 On Saturday evenings in Ontario, young Latines enjoyed conjunto at the local dance hall.100 On Sundays, they went to church, maybe saw a movie, and ended up socializing with friends at Beck-Kiwanis Park. Like other spaces in towns and cities across the region—movie theaters, dance halls, churches, restaurants, even streets and sidewalks—this park accrued meaning. “We felt like we had a place,” Mercedes Rivera recalled. “We belonged there.”101

Latines claimed spaces in towns and cities even more visibly through public fiestas that featured food, music, and dancing. The first fiestas in the region occurred during the 1940s, when braceros organized celebrations of Dieciséis de Septiembre and Cinco de Mayo.102 During the 1950s and 1960s, Tejano families across the region organized even larger events. The business owner Tony Rodriguez, for example, recruited volunteers from Nampa and nearby communities in 1957, and together they organized an annual Dieciséis de Septiembre fiesta in Caldwell that drew thousands of people for a parade, food, live music and other entertainment, and an evening dance.103

The region’s most enduring fiesta originated in 1964, when Woodburn’s white business owners selected a weekend in August to signal their receptiveness to ethnic Mexicans. After Tejanos inherited leadership of Woodburn’s annual Fiesta Mexicana, attendance grew, but it also evolved. By the 1970s, Tejano families outnumbered white families. By the 1980s, Mexican immigrants outnumbered Tejanos. Conjunto thus gave way to the mariachi and banda music that Mexican immigrants preferred. A baseball tournament remained, but soccer garnered even more interest.104 As the interdisciplinary scholar Elizabeth Flores concludes, this evolution allowed all Latines “to feel a sense of belonging.”105 Indeed, from the mid-1960s through the 1980s and beyond, Latines claimed spaces in Woodburn through their participation in its annual fiesta. As with other spaces in towns and cities across the Pacific Northwest, these claims were multigenerational, and they reflected the growing diversity of the region’s Latine population.

Latine business owners like Tony Rodriguez helped organize these fiestas. As other Latines opened restaurants and other small businesses, the importance of their leadership— and the importance of the places they created—continued to grow.106 Rogelio and Armandina Medina, for example, opened Mexico Lindo in downtown Woodburn in 1966. They sold Mexican imports and made the store “a good place to congregate,” but they also contributed to Fiesta Mexicana and became community advocates.107 Manuel Barrón’s barbershop was already a hub in south Seattle when he cofounded the Club Social Hispano Americano in 1967. Members organized dances in rented venues and picnics in local parks, and they bolstered community solidarity in the face of discrimination.108 Tony Rodriguez himself took up the same fight in the early 1960s, aft er his daughter saw a No Mexicans sign in a Nampa restaurant and came home in tears—a reminder that Latine claims on spaces did not go unchallenged. Rodriguez, for his part, responded by organizing fellow veterans and other faith and community leaders who then lobbied successfully for a state law prohibiting discrimination in places of public accommodation.109

Older Latines who claimed spaces and made places throughout the region during the 1950s and 1960s did not necessarily intend to create loci for multigenerational activism. Yet some younger Latines realized that is what they had done—and members of their generation began to do so more deliberately. Their eff orts from the mid-1960s through the 1980s drew inspiration from the farmworker movement and the Chicano movement, both of which emphasized community organizing, labor-rights and civil- rights advocacy, and cultural pride.110 As the geographer Juan Herrera suggests, the activism associated with these social movements “happened in and through a relationship with space” and often resulted in “the making of ‘place.’”111

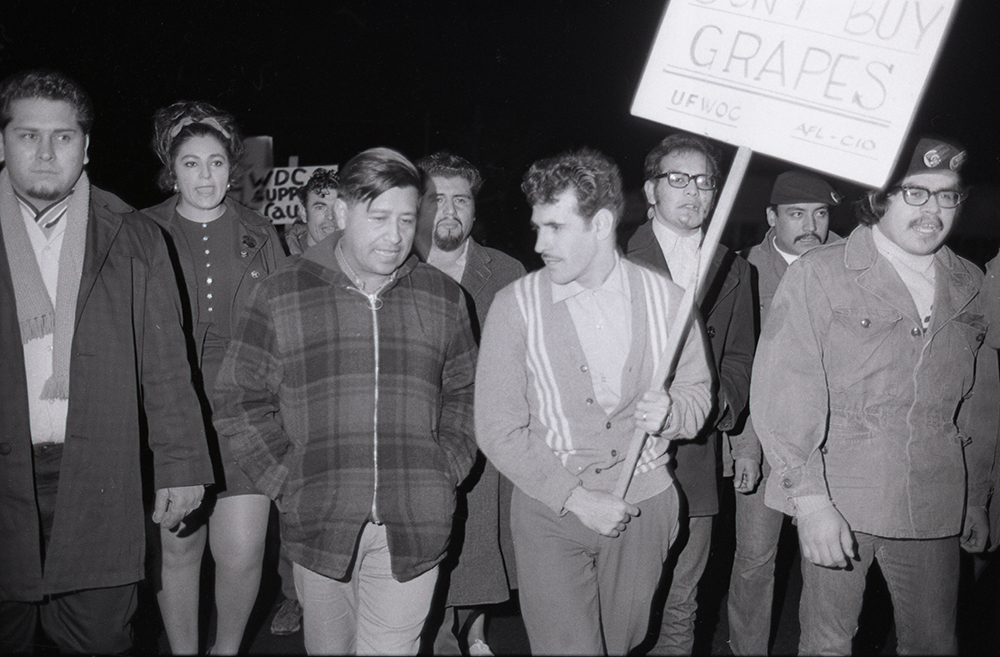

In the Pacific Northwest, this activism originated in 1965 when farmworker advocacy groups such as the Yakima Valley Council for Community Action (yvcca) began to secure federal antipoverty funding from the Office of Economic Opportunity. These groups were predominantly white, but younger Latines who identified as Chicanos or Chicanas soon exercised more leadership.112 Tomás Villanueva, for example, was a former farmworker finishing his studies at Yakima Valley College when he joined the yvcca staff in 1966. Hoping to learn more about the farmworker movement, he and a coworker drove to Delano, California, to meet with Cesar Chavez. They “saw some of the things that Brother Cesar was doing, the gasoline co-ops and things.” Chavez told them, “Nothing is going to change in the conditions of farmworkers unless farmworkers themselves do the changes.”113 Thus inspired, Villanueva started a co-op store inside a new community center in Toppenish, one of seven centers the yvcca opened in the mid-1960s.114 When the co-op outgrew this space, Villanueva found a nearby building that was fire damaged but otherwise “fit us perfectly.”115 He and other volunteers repaired the building in lieu of the first year’s rent and proudly opened the United Farm Workers Co-op in 1967. The yvcca community centers offered valuable services, but this co-op building became a locus of farmworker organizing and activism in the years to come.116

Farmworker advocates in the Willamette Valley formed the Valley Migrant League (VML) in 1965 and likewise received federal funding for seven opportunity centers. The VML staff offered adult education programs, daycare, and other services in these centers, but some of the white staff members expressed condescending views. They blamed the poor conditions of labor camps, for example, on migrant workers who “naturally mistreat facilities.”117 The resulting tensions led to the departure of Latine staff members such as Emilio Hernández, who had continued to work as a farm foreman in Forest Grove when he became active at the VML center in Hillsboro. When the VML fired the director of that center in 1966, Hernández and other Latines also left and soon launched Volunteers in Vanguard Action (viva).118 Sharing Cesar Chavez’s self-help philosophy, viva opened a co-op gas station in Hillsboro and a community center in Forest Grove, both staffed by former farmworkers. “Nobody can do it for us,” the viva cofounder José Morales insisted. “Only we who have experienced [poverty]…can end this so-called war on poverty.”119

Young Chicanos such as Sonny Montes stayed with the VML and eventually secured leadership positions, but farmworker advocacy efforts in Idaho reflected the broader pattern. The Southwest Idaho Migrant Ministry created Idaho Workers Services and received federal funding in 1965. Leadership shifted to Treasure Valley Community College (tvcc) but remained predominantly white until 1970, when a farmworkers’ strike near Caldwell fueled a rupture. Latine organizers left tvcc and formed the Idaho Migrant Council because, as Humberto Fuentes insisted, farmworkers “need a voice.” As Fuentes and other organizers opened community centers and offered services that improved the lives of farmworkers, they asserted their right to “have a say so in the way things are run.”120

The Chicano movement propelled these efforts even further. Members of the Black Student Union (BSU) at the University of Washington helped lay a foundation in 1968, when they noted that the student body of thirty thousand included only 10 Mexican Americans. The BSU members made their way to the Yakima Valley that summer and, with Tomás Villanueva’s help, recruited 35 new Mexican American students.121 A year later, Antonia Castañeda built on this foundation. After graduating from Granger High School and Western Washington University, Castañeda had entered the UW graduate program in Spanish in 1968. She emerged as a student leader alongside her fellow graduate students Tomás Ybarra-Frausto and Roberto Maestas, so administrators hired her to recruit more students. Joined by four undergraduates, she spent the summer of 1969 returning to familiar spaces and places in the Yakima Valley: “We went to dance halls. We went to churches. We went to labor camps. We went to…the high schools.”122 They recruited 90 Mexican American students and “established a community” that helped transform the university and, more visibly, transcended it.123

Indeed, these students lobbied for Chicano studies and an ethnic cultural center that would include what the historian Erasmo Gamboa—a member of the 1968 cohort—described as their own “separate and identifiable space.”124 But they also engaged with national organizations such as Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA) and embraced an ethos of community empowerment and cultural pride.125 This, in turn, drew many of them back to the Yakima Valley. Tomás Ybarra-Frausto thus spent most of 1970 turning a former Catholic chapel in Granger into an educational and cultural center. He and fellow students curated exhibits of Mexican pottery and textiles, taught classes, produced plays, and christened the building a calmécac—a school for Aztec nobility.126 Other students launched a voter registration drive in the Yakima Valley that summer, and the United Farm Workers Co-op provided a base of operations. When these students pivoted to support a hop workers’ strike that fall, they again saw the importance of claiming spaces—in this case, the roads around the hopyards where they joined workers on the picket lines.127

The Chicano movement also drew UW students out into Seattle, and Roberto Maestas helped lead the way. After finishing his master’s degree, Maestas was directing the English as a Second Language (ESL) program at South Seattle Community College in 1972 when administrators terminated the program. Seeking somewhere to relocate, Maestas identified the vacant Beacon Hill School. When city officials rejected his proposal to reopen the substantial three-story building as a community center, Maestas and a group of ESL students entered the building and announced their refusal to leave. They occupied and thereby claimed this space, with the hope of making a place. Students from UW and a multiracial coalition of several hundred allies joined them.128 They also endorsed Maestas’s proposal to rename the building El Centro de la Raza. It would be a place for “all the people,” but one in which Latines in particular would “have their needs understood and addressed.”129 In 1973 the city finally agreed to allocate funding to renovate the building and provide ESL classes, vocational training, a food bank, and other services for those in need.130

As the historian Diana Johnson explains, El Centro’s work through the 1980s continued to prioritize “the social service needs of ethnic Mexicans, elements of Chicano nationalism, and multiracial solidarity.”131 Similar eff orts unfolding in the region’s agricultural areas emphasized culture, education, and health care. Emilio and Hortencia Hernández and other viva cofounders, for example, raised funds through monthly dinners and dances; purchased an old house in Cornelius, Oregon; and opened Centro Cultural of Washington County in 1972. With support from local employers, they offered cultural activities, ESL classes, and vocational training.132 They were reminded that summer that their claims on space remained tenuous when a bartender in nearby Forest Grove ejected three Chicanos for speaking Spanish in violation of the bar’s English-only rule. Such claims remained significant—and constitutionally protected—but Centro Cultural provided a sure sense of belonging because it was a place of their own.133 Enedelia Hernández Schofield, the daughter of Emilio and Hortencia, later explained that Centro Cultural was “a place where you could…[share] music you wanted to hear…food you wanted to eat and stories that you had in common.”134 Its vitality fueled fundraising eff orts, leading to the construction of a new building in downtown Cornelius in 1981 and the expansion of services thereafter.135

Perhaps the boldest effort to make a place for Latine education during these decades reflected the leadership of Sonny Montes. Born in Texas in 1944, Montes settled in Cornelius in 1966 and soon joined the staff of the Valley Migrant League. When Emilio Hernández and other Latines left the VML, Montes stayed, gained leadership experience, and gradually transformed the organization.136 Montes had taken an administrative position at Mount Angel College in 1972 when mismanagement led to a loss of accreditation but also an opportunity to reinvent the college as one that would serve working-class Chicanos and Chicanas. Announcing a new name in 1973, Colegio Cesar Chavez, Montes and other administrators embraced the social justice struggles of the farmworker movement and the Chicano movement. The Colegio lacked funds to renovate the aging buildings on its five-acre campus, but until it finally succumbed to chronic financial problems in 1983, the Colegio continued to connect hundreds of Latine students, faculty, staff , and community members from the Willamette Valley and beyond, many of whom used the buildings—and the spaces within, around, and between them—for classes, cultural events, and other community gatherings.137

When Latines focused on health care, they drew upon these kinds of connections. Members of the United Farm Workers Co-op, for example, helped Tomás Villanueva open a clinic in Toppenish, Washington, in 1970 and pursue federal funding for what would grow into the multilocation Yakima Valley Farm Workers Clinic.138 The Valley Migrant League secured similar funding for Salud de la Familia, which opened its first clinic near downtown Woodburn, Oregon, in 1972.139 After six-year-old Virginia Garcia died in a Washington County labor camp in 1975 because hospital staff failed to communicate medication instructions to her Spanish-speaking parents, Emilio Hernández decided to open a clinic in the Centro Cultural house—the original home of what would become the multilocation Virginia Garcia Memorial Health Center.140 Students at the UW saw the same need for affordable, bilingual services in Seattle. Drawing on his connections to MEChA, El Centro de la Raza, and the clinic in Toppenish, Rogelio Riojas led a push for federal funding in 1976. Joining forces with a group from Marysville, they opened the original Sea Mar clinic in south Seattle in 1978, the first of many that would open in the years to come.141 Working toward similar goals, Humberto Fuentes and the Idaho Migrant Council opened five clinics between 1976 and 1980.142

As activist placemaking continued through the 1980s, it reflected the diversity of a Latine population that included growing numbers of documented and undocumented immigrants from throughout Latin America. The Willamette Valley Immigration Project (wvip), for example, originated in 1976, when Cipriano Ferrel and other students at Colegio Cesar Chavez decided to respond to a growing number of Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) raids on labor camps and other spaces associated with Latine immigrants. The wvip organizers assisted those facing deportation and soon opened an office in an old house near downtown Woodburn.143 A sharp increase in the number of undocumented Indigenous immigrants employed—and exploited—as reforestation workers during the early 1980s fueled the transformation of the wvip into a labor union, Pineros y Campesinos Unidos Noroeste (pcun), in 1985. After President Ronald Reagan signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act (irca) in 1986, the number of immigrant workers pcun assisted with amnesty paperwork grew into the thousands, driving the need for larger offices. The union kept the old house but also bought a former church building next door, remodeled it, and made it another locus for diverse, multigenerational organizing and activism. Both of these buildings thus gained significance, as did the spaces associated with them.144

Latines such as Ricardo García likewise continued to transform buildings in the Yakima Valley into significant places for organizing and activism. Born in Texas, García settled in the Yakima Valley and became active in the farmworker movement and the Chicano movement during the 1960s. As executive director of a community organization, Northwest Rural Opportunities (NRO), he helped launch Radio Cadena in 1976.145 Originally broadcasting through a station in Seattle, Radio Cadena soon received its own license and call letters (kdna) and sought a home in the Yakima Valley. When NRO purchased an old two-story brick building in Granger, it offered studio space to Radio Cadena, which began broadcasting Spanish-language music, news, and other programming to Latines throughout the Yakima Valley in 1979.146 In the coming years, whenever the station received word of an impending INS raid, the host would play a song about la migra (a reference to immigration officials) and dedicate it to the targeted town. When irca became law in 1986, the station provided information about amnesty procedures. When farmworker activism reignited in the Yakima Valley the same year, the station publicized marches, strikes, and boycotts.147 As Monica De La Torre notes, the NRO building itself became “a central place for information, assistance, entertainment, and convivencia,” but so did the spaces nearby.148 The NRO constructed a traditional kiosko (gazebo) and plaza near the building, and Radio Cadena hosted health fairs, tardeadas (afternoon gatherings) with music and food, and other events that served and strengthened the community during the 1980s and beyond.

The historian Luke Sprunger has argued that Latines who developed Centro Cultural and the Virginia Garcia Memorial Health Center “asserted a right to belong in Washington County.”149 The same holds true for those who developed homes, small businesses, community centers and co-ops, cultural and educational centers, health clinics, and other places throughout the Pacific Northwest from the 1960s through the 1980s. The same also holds true for those who claimed spaces in the region’s fields and orchards, labor camps, movie theaters, dance halls, churches, restaurants, parks, and even the streets and sidewalks where they socialized and mobilized. Their efforts to make places were more visible and enduring than their efforts to claim spaces, but all these efforts reflected assertions of belonging and of a right to belong in the region as a whole. Indeed, by the 1990s, many older Latines had begun to remake the Pacific Northwest into a region in which they felt a sense of belonging—they had made the region their home.150 As younger Latines grew up in the region, many of them did so with the same sense of belonging. Reflecting on his experiences growing up in Quincy in the 1970s, the historian Jerry García thus recalls that “Mexican culture [was] alive and well” in the spaces and places of his community’s faith, language, music, food, sporting events, and social gatherings. “And, yet,” he concludes, the Pacific Northwest was “the region that defined my experience and made me who I am today.” The people of the region did not always treat him well, but the region was his home.151

These developments continued through the 1990s and into the new century. The region’s Latine population remained diverse and diffused, but it also grew significantly in size and visibility, and that brought new population concentrations in cities and towns and new levels of economic and political power—not to mention new anxieties on the part of people like Dave Ettl and his radio show listeners. Whether newly arrived or long-established, Latines throughout the region continued to claim spaces and make places, and many of their efforts reflected an enduring ethic of community service and solidarity. Many of these efforts also became intertwined with each other. Ultimately, Latines made themselves at home in the region. In doing so, they made the region their home.

Scholars have identified the Pacific Northwest as a “new destination” for Latine immigrants during and after the 1990s.152 The region was not entirely new as a destination, but a new influx of documented and undocumented immigrants—plus the arrival of migrants from the Southwest and the natural increase of established families—did drive the region’s Latine population to nearly 820,000 in 2000 and then beyond 1.4 million by 2010.153 Working-class Mexican and Central American immigrants in particular continued to arrive under the auspices of irca, which had allowed the family members of amnestied immigrants to receive visas. Economic turmoil in Mexico before and aft er the adoption of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994 led growing numbers of entrepreneurs and professionals to join the immigrant stream as well, and many of them ended up in the Pacific Northwest.154 Census data suggests that newly arriving immigrants settled throughout the region but also that second- and third-generation Latines outnumbered them in the region’s largest cities.155

During and after the 1990s, Latines throughout the Pacific Northwest continued to claim spaces in a growing variety of industries and professions. They also claimed religious, educational, cultural, and recreational spaces. As in prior decades, many of these claims were ephemeral, but many were now more visible—in part because of the activism of those prior decades. The life and work of María Alanís Ruiz offer an illustration. Born in Mexico, she settled with her parents and siblings in the Willamette Valley in the 1960s. The family worked in the fields and lived in labor camps, but a Chicana organizer from the VML inspired Alanís Ruiz’s enrollment at the University of Oregon, where she embraced Chicana feminist activism. After graduating in 1974, she worked as a recruiter for Colegio Cesar Chavez until 1980, when she began a long career as an admissions officer at Portland State University. Even as her claims on spaces at the university faced racist and sexist challenges, Alanís Ruiz continued her work in the community.156 In 1985 she led the effort to launch Portland’s Cinco de Mayo fiesta. It started with just a few booths in Ankeny Plaza but grew substantially, drawing several hundred thousand visitors every year by the early 2000s.157 Norma Cárdenas credits Alanís Ruiz and the city’s celebration of Cinco de Mayo for giving Latines a visible and enduring way “to create space, forge memory, and reinforce…[their] identity and culture.”158

Latine entrepreneurs throughout the region also continued to make places. They had greater access to capital, and they invested it in businesses that succeeded because they served and strengthened their communities.159 Ana Castro and her sister Aminta Elgin, for example, fled El Salvador during the 1980s and made their way to Seattle. Both women had growing families and successful careers as surgical technicians, but in 1996 they secured home-equity loans and opened Salvadorean Bakery in White Center, a neighborhood with a concentration of Salvadorean families. The business remained modest, but that was part of its appeal. “Salvadorean Bakery is small,” Castro noted in 2020, “but a lot of the Salvadorean people who come here feel like they’re at home.”160 Likewise, the brothers Ranulfo and Pablo Juárez settled in the Willamette Valley in the 1980s, worked in managerial positions, and opened a convenience store in Salem in 1998. Befriending Ranulfo in the early 2000s, Peter Wogan found El Palmar well-stocked with Mexican foods, rental videos, and merchandise and enlivened by Ranulfo’s warm interactions with a steady stream of regulars.161 It “was like a Mexican town plaza, a public space where people went out to stroll…and talk with relatives and neighbors.” El Palmar “wasn’t just a convenience store,” Wogan realized, “it was a community.”162

Myriad efforts to make other places—housing, health clinics, and cultural centers—extended the community organizing and activism of prior decades. In 1990 pcun connected with other organizations to create the Farmworker Housing Development Corporation (fhdc), which then secured $2 million to build Nuevo Amanecer in Woodburn, the first of several affordable housing complexes located in the Willamette Valley. Completed in 1994, Nuevo Amanecer was designed for Latine families, with 90 apartments featuring ground-floor entries and vaulted ceilings, community facilities, playgrounds, and gardens. As Lise Nelson has argued, the fhdc thus created “not just housing but spaces of belonging.”163 Sea Mar and the Yakima Valley Farm Workers Clinic continued to open scores of clinics, including the latter’s $15 million facility in Toppenish, inspired by the architecture of central Mexico and completed in 2015.164 A year later, El Centro de la Raza secured $45 million to develop affordable housing adjacent to its home in south Seattle, with 112 apartments and a plaza named for Roberto Maestas.165 The Hispanic Cultural Center of Idaho worked with the city of Nampa to build its new home in 2003.166 Radio Cadena helped build the Northwest Communities Education Center—its own new home in Granger—in 2009.167 Most recently, Sea Mar opened its Museum of Chicano/a/Latino/a Culture in south Seattle in 2019.168

In many cases, Latine efforts to claim spaces and make places became intertwined. In Seattle, for example, community organizers sought to assist unhoused Latine day workers who struggled because they did not speak English. In 1994 these organizers founded what later became Casa Latina. As their services grew beyond ESL classes to encompass day worker and domestic worker dispatch and women’s rights advocacy, they claimed several spaces around the city, including a downtown office, a church basement, and an unheated trailer in a parking lot. In 2007 they finally acquired a $1.2 million property near the city’s Central District and Chinatown–International District where they could build new facilities and thus consolidate their services.169 When immigrants’ rights advocates began conducting annual marches in Seattle in 2006—asserting claims on streets and sidewalks—Casa Latina provided the places where many of them gathered to prepare.170

Decades earlier, Sergio Marquez had immigrated from Mexico, made his way to the Yakima Valley, and claimed spaces in the apple orchards near Wapato. After working for the same orchardist for 25 years, he borrowed $400,000 and bought the 106-acre orchard, all the equipment, and a modest house on the property in 2004. Marquez expanded his operations and soon employed around 50 other Mexican immigrants—workers who claimed spaces in a place he had made.171 Other Latines who had acquired land in the region’s rural areas in prior decades often created ranchitos, working for wages but also raising chickens and pigs and growing produce to sell on the side.172 But the number of Latines who were commercial farmers and orchardists began to grow significantly during and after the 1990s (surpassing 1,400 in Oregon alone during the 2010s).173 Alexander Korsunsky concludes that many of these new farmers and orchardists wanted “to make…places in which to create an aspirational good life understood in terms of hard work and independence…and the ability to enjoy the fruits of a life lived outdoors.”174 Profits were important, but so was a livelihood that allowed them to create a sense of place and belonging—to host gatherings, “to share food and stories, and to build community.”175

Latine efforts to claim spaces and make places intertwined perhaps most visibly in the region’s smaller cities and towns, many of which began to see the Latine share of the population rise well beyond 50 percent.176 Woodburn, one of the first cities in which this happened, saw its total population grow during the 1990s from 13,400 to 20,100. The city’s Latine population grew from 4,200 (32 percent of the total) to 10,060 (just over 50 percent), a trajectory that continued into the 2010s.177 When Carlos Maldonado and Rachel Maldonado studied the “Mexicanization” of Woodburn, they highlighted the transformation of the city’s downtown core—the longtime home of Mexico Lindo, Salud de la Familia, and pcun. A few more Latine-owned businesses opened in downtown Woodburn during the 1980s, but then 34 businesses opened during the 1990s. More than half of those survived into the 2000s, when yet another 37 businesses opened, ranging from restaurants, bakeries, and carnicerías to import stores, clothing stores, music stores, hair salons, money wiring services, and auto repair shops. Musicians, vendors selling ice cream and corn on the cob, and other mobile entrepreneurs also contributed to the “enacted environment” by claiming streets and sidewalks—the spaces within, around, and between rejuvenated downtown buildings.178 When city leaders developed a downtown park in 2005, they modeled it after a traditional Mexican plaza, with a kiosko, fountain, and palm trees.179

Documenting similar developments in and beyond downtown Pasco, Washington, the geographer Yolan- da Valencia argues that a sense of place emerges from sights, sounds, and tastes that evoke or create fond memories. During and after the 1990s, Mexicanized or Latinized places like downtown Woodburn and downtown Pasco began to offer such experiences for Latines in the Pacific Northwest.180 In doing so, these places affirmed that the region had been changing, in large part because its people had been changing. By the 2010s, Latine immigrants had been arriving in the region for more than a century, bringing strong values, family ties, and faith traditions as well as growing desires to settle in the region, create homes and communities, and enjoy a sense of belonging. Longtime residents such as Eva Castellanoz have been passionate in expressing these desires. Born to Indigenous parents in Mexico, Castellanoz grew up in Texas but settled in eastern Oregon, where her father helped her build a home in the 1960s. “Through the next forty years,” the writer Joanne Mulcahy explains, Castellanoz became an accomplished folk artist and healer and raised nine children to whom she “passed on a fierce attachment to eastern Oregon.”181 Castellanoz credits her own father for that attachment. Driving with Mulcahy outside of Nyssa, she pointed to sugar beet fields like those cultivated by the region’s first Mexican immigrants. “This was my daddy’s dream, to have a home here,” she said. “I want to be part of the realization of that dream.”182

The field of historic preservation does better with people’s buildings than with their dreams. Significant buildings are worth preserving, but a preservation field that continues to focus primarily on buildings will continue to lose opportunities to more fully preserve places, spaces, and stories—to more fully preserve history, including the history of the Pacific Northwest. In an era of heightened awareness about the consequences of climate change, a conviction that the Senegalese environmentalist Baba Dioum articulated in 1968 has become better known: “In the end we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught.”183 The members of Latinos in Heritage Conservation and many like-minded colleagues recognize that if we preserve not just the buildings but the history and heritage we love, then we will be better equipped to teach understanding and thereby inspire cross-cultural appreciation and respect. We also know the opposite is true. If other preservationists choose not to preserve our history and heritage—including buildings that seem to have lost some of their physical integrity—they signal that our history and heritage do not deserve appreciation and respect. Ultimately, this is why I present certain arguments to audiences that include more preservationists than historians. Buildings matter, but people matter more.

Raymond W. Rast is an associate professor of history at Gonzaga University. He also serves as a board member for Latinos in Heritage Conservation and the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation. Rast holds a PhD in history from the University of Washington. His previous publications focus on ethnic Mexicans, placemaking, and historic preservation.

Citations:

1. Latinx has come into common usage among scholars as a term that is inclusive of males, females, and non–gender-binary people, but the X makes the term challenging for Spanish speakers. Some Spanish-speaking scholars thus have proposed the alternative Latine, which is more consistent with the language and, as with the Spanish word estudiante, maintains a gender-neutral inclusivity.

2. Dionne Searcey and Robert Gebeloff, “The Divide in Yakima Is the Divide in America,” New York Times, Nov. 19, 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/11/19/us/politics/yakima-washington-racial-differences-2020-elections.html (accessed Nov. 15, 2023).

3. Dave Ettl quoted in ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Washington Trust for Historic Preservation and Artifacts Consulting, Inc., “Latino Heritage of Greater Seattle: Intensive Level Survey Documentation and Illustrated Historic Context Statement,” May 2019, Department of Archeology and Historic Preservation, dahp.wa.gov/sites/default/files/Seattle_Latino_ContextStudy_2019.pdf; Washington Trust for Historic Preservation and Artifacts Consulting, Inc., “Yakima Valley Latino Study Survey: Reconnaissance Level Survey Documentation and Historic Context Statement,” October 2016, Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, dahp.wa.gov/sites/default/files/YakimaValley_Latino_ContextStudy_2016.pdf.

6. For practical reasons, I define the Pacific Northwest as Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.

7. Douglas S. Massey and Chiara Capoferro, “The Geographic Diversification of American Immigration,” in New Faces in New Places: The Changing Geography of American Immigration, ed. Douglas S. Massey (New York, 2008), 27, 38 (qtn.).

8. Census data for 2000-10 drawn from United States Census Bureau, data.census.gov. Rate of growth since 2010 and estimates for 2020 drawn from www.census.gov/quickfacts/WA, www.census.gov/quickfacts/OR, and www.census.gov/quickfacts/ID.

9. “Yakima Valley Latino Study Survey,” 7-8; “Latino Heritage of Greater Seattle,” 1.

10. Raymond W. Rast, “The Latinization of Landscapes in the Pacific Northwest,” annual conference of the Society for Architectural Historians, April 30–May 1, 2020, online.

11. Jesus J. Lara, Latino Placemaking and Planning: Cultural Resilience and Strategies for Reurbanization (Tucson, Ariz., 2018); A. K. Sandoval-Strausz, Barrio America: How Latino Immigrants Saved the American City (New York, 2019).

12. Raymond W. Rast, “Cultivating a Shared Sense of Place: Ethnic Mexicans and the Environment in Twentieth-Century Kansas City,” Diálogo: An Interdisciplinary Studies Journal, Vol. 21 (Spring 2018), 43- 44.

13. National Park Service, Cesar Chavez Special Resource Study and Environmental Assessment (San Francisco, 2012); National Park System Advisory Board, American Latinos and the Making of the United States: A Theme Study (Washington, D.C., 2013).

14. Paul Groth, “Frameworks for Cultural Landscape Study,” in Understanding Ordinary Landscapes, ed. Paul Groth and Todd W. Bressi (New Haven, Conn., 1997), 1.

15. Theresa Delgadillo, “Unsustainable Environments and Place in Latinx Literature,” in Building Sustainable Worlds: Latinx Placemaking in the Midwest, ed. Theresa Delgadillo et al. (Urbana, Ill., 2022), 26. See also Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (Minneapolis, Minn., 1977).

16. Richard H. Schein, “Race and Landscape in the United States,” in Landscape and Race in the United States, ed. Richard H. Schein (New York, 2006), 5.

17. See, for example, Eric Avila, Popular Culture in the Age of White Flight: Fear and Fantasy in Suburban Los Angeles (Berkeley, Calif., 2004), 1.

18. When referring to people of Mexican descent regardless of their places of birth, here and elsewhere I follow scholarly convention in using the term “ethnic Mexican.”

19. Albert Camarillo, Chicanos in a Changing Society: From Mexican Pueblos to American Barrios in Santa Barbara and Southern California, 1848-1930 (1979; rpt. Dallas, Texas, 2005), 53-78 (53, qtn.).

20. James Rojas, “The Enacted Environment of East Los Angeles,” Places, Vol. 8 (1993), 42.

21. Ibid., 47.

22. Ibid., 42.

23. Ibid., 53.

24. James Rojas, “The Cultural Landscape of a Latino Community,” in Schein, ed., Landscape and Race, 182.

25. Raúl Homero Villa, Barrio-Logos: Space and Place in Urban Chicano Literature and Culture (Austin, Texas, 2000), 6 (qtns.), 7.

26. Lawrence A. Herzog, “Globalization of the Barrio: Transformation of the Latino Cultural Landscapes of San Diego,” in Hispanic Spaces, Latino Places: Community and Cultural Diversity in Contemporary America, ed. Daniel D. Arreola (Austin, Texas, 2004), 106.

27. Ibid.

28. See Raymond W. Rast, “A Matter of Alignment: Methods to Match the Goals of the Preservation Movement,” National Trust for Historic Preservation Forum Journal, Vol. 28 (Spring 2014), 13-22.

29. For an overview, see John H. Sprinkle, Jr., Crafting Preservation Criteria: The National Register of Historic Places and American Historic Preservation (New York, 2014), 45-67.

30. Stewart Brand, How Buildings Learn: What Happens after They’re Built (New York, 1994), 2.

31. Jules D. Prown, “Material/Culture: Can the Farmer and the Cowman Still Be Friends?” in Learning from Things: Method and Theory of Material Culture Studies, ed. W. David Kingery (Washington, D.C., 1996), 19.

32. Ibid., 20.

33. Chatelain quoted in Barry Mackintosh, “The National Park Service Moves into Historical Interpretation,” The Public Historian, Vol. 9 (Spring 1987), 55.

34. These were not the first Latines to live in the Pacific Northwest. During the second half of the 19th century, a small number of Mexican miners, mule packers, and cattle drivers found work in the region. See Erasmo Gamboa, “Latino Past and Present in Washington State History [Part One],” Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 34 (Winter 2020- 21), 16-17.

35. Acuña quoted in Chicano! A History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement, documentary, directed by Hector Galan (Los Angeles, 1996), part 2.

36. Erasmo Gamboa, Mexican Labor and World War II: Braceros in the Pacific Northwest, 1942-1947 (1990; rpt. Seattle, 2000), 6-10; Erasmo Gamboa, ed., Voces Hispanas: Hispanic Voices of Idaho (Boise, Idaho, 1992), 6-7, 9-12.

37. Guadalupe Friaz, “A Demographic Profile of Chicanos in the Pacific Northwest,” in The Chicano Experience in the Northwest, ed. Carlos S. Maldonado and Gilberto García (Dubuque, Iowa, 1995), 41-42.

38. Ibid.

39. Errol D. Jones and Kathleen Hodges, “A Long Struggle: Mexican Farmworkers in Idaho, 1918-1935,” in Memory, Community, and Activism: Mexican Migration and Labor in the Pacific Northwest, ed. Jerry García and Gilberto García (East Lansing, Mich., 2005), 46-47; Erlinda V. Gonzales-Berry and Marcela Mendoza, Mexicanos in Oregon: Their Stories, Their Lives (Corvallis, Oreg., 2010), 22-23, 27-31.

40. Carlos B. Gil, “Washington’s Hispano American Communities,” in Peoples of Washington: Perspectives on Cultural Diversity, ed. Sid White and S. E. Solberg (Pullman, Wash., 1989), 171-73; Carlos Maldonado, “Mexicanos in Spokane, 1930-1992,” Revista Apple, Vol. 3 (Spring 1992), 120.

41. Gamboa, Mexican Labor; Friaz, 43-44; Johanna Ogden, “Race, Labor, and Getting Out the Harvest: The Bracero Program in World War II Hood River, Oregon,” in Memory, Community, and Activism, ed. García and García, 129-52; Gonzales-Berry and Mendoza, 31-47; Mario Jimenez Sifuentez, Of Forests and Fields: Mexican Labor in the Pacific Northwest (New Brunswick, N.J., 2016), 10-35.

42. Gamboa, Mexican Labor, 120-25; Carlos Saldivar Maldonado, “Testimonio de un Tejano de Oregon: Contratista, Julian Ruiz,” in Memory, Community, and Activism, ed. García and García, 220-26; Josué Quezada Estrada, “Texas Mexican Diaspora to Washington State: Recruitment, Migration, and Community, 1940-1960,” MA thesis (Washington State University, 2007), 52-61; Gonzales-Berry and Mendoza, 56-58; Luke Sprunger, “‘This is Where We Want to Stay’: Tejanos and Latino Community Building in Washington County,” Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 116 (Fall 2015), 283; Sifuentez, 23-33.

43. Errol D. Jones, “Latinos in Idaho: Making Their Way in the Gem State,” in Idaho’s Place: A New History of the Gem State, ed. Adam M. Sowards (Seattle, 2014), 211.

44. Estrada, 16; Sifuentez, 41; Gil, “Washington’s Hispano American Communities,” 170-71; Jones, 210-11.

45. Irene Castañeda, “Crónica de Cristal/Chronical of Crystal City,” El Grito, Vol. 4 (Winter 1971), 51-52.