Women on the Waterfront: Ruth Reeber

By Ruth Reeber, Lead Test Engineer

I am a Lead Test Engineer at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, and my job is cool. Well, sometimes. Some days it’s really cool, like when you get to go underway on a submarine to test equipment at different depths! Other days it’s less cool, like when instead of blowing the raw sewage overboard, the very tired mechanic accidentally blows it back up the toilets and drains from whence it came, and you awaken from a desperately needed nap to a brown waterfall about ten feet aft of your rack and an announcement calling all off-watch personnel to help clean up. Those were, as it turns out, the same day.

Or she would, if nine years of working at the Shipyard hadn’t made that about as novel as the bus I take from the parking lot to the pier every morning. Time in erodes awareness of; after a while, it stops being a marvel of engineering and becomes the place I should have been seven minutes ago but I really wanted to finish my coffee so I left the house late.

Frankly, a lot of my job is paperwork. I work primarily on aircraft carriers, so I do most of this paperwork sitting in an office trailer, one of several nearly identical modular buildings that can be picked up by a crane from the pier and deposited on the aircraft elevator of a carrier, then moved into position in the hangar bays by (very big) forklifts. As such, while my inner eight-year-old is mildly dismayed that I work at a desk in an office, she gets a kick out of the fact that I scramble across a gangway every morning to go to work on a floating city.

The short, unsexy explanation of my job is this: when a US Navy ship arrives at the Shipyard for a scheduled maintenance cycle, my work group (Code 246) is responsible for working with the crew to get things ready to take apart, authorizing work in our area of responsibility, and retesting everything once the work is done. That’s paperwork (and acronyms) aplenty, but it’s also a lot of people-work: every plan we make to secure equipment or retest it requires coordination and concurrence from the ship’s crew, who must grind through their own sizeable worklist while monitoring the ship’s nuclear reactors, accomplishing training, and a thousand other mandates frequently disrupted by the necessities of, say, tearing apart a division’s normal office space to resurface the deck. Coordination with the other engineering groups, the shop workers performing the work, contractors based on the other side of the country—this is as much the job as any of the technical skills my engineering degree imparted.

Surprise, inner eight-year-old! It’s conflict resolution all the way down. Conflicting priorities. Conflicting work items. Conflicting schedules. Conflicting personalities, inevitably. Conflicting reference material. Learning how to resolve (or at least mitigate) conflict has been the most significant on-the-job skill I’ve learned in my nine years and change at the Shipyard, and I’m still learning it.

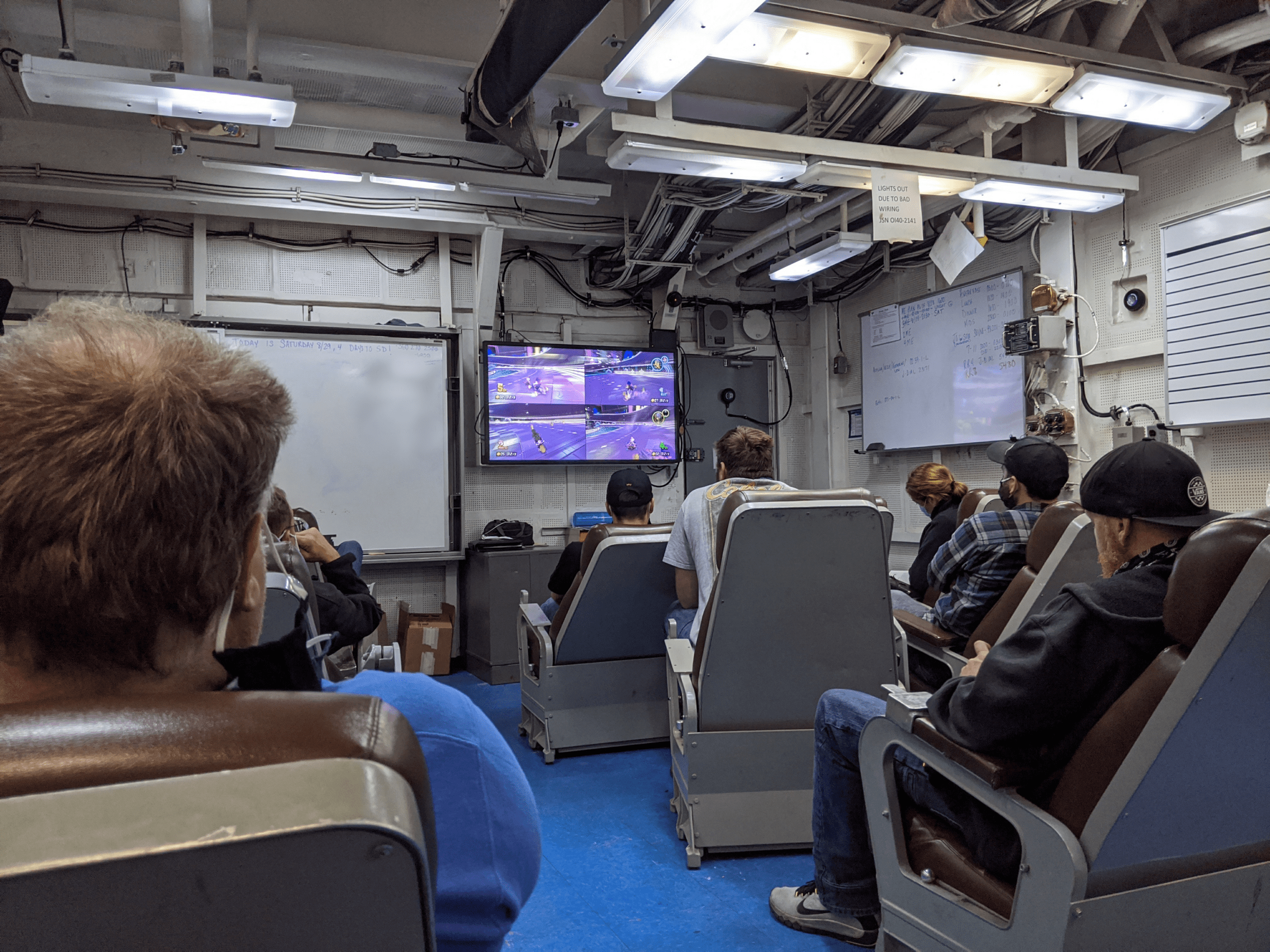

Good days (for me) are the ones marked by progress: work started, work finished, tests completed. Or simply by solving a problem or resolving confusion, even when it’s as simple as these handwheels are swapped or the fuses were never reinstalled, that’s embarrassing. The best days, though, are at the end of a long maintenance period, when the temporary lighting and the plywood and the staging begins to disappear, and the ship begins to be a ship again instead of a floating construction zone. There’s something deeply satisfying to me about seeing the propulsion plant come back to life, matched only by the really fun testing that can only be done out to sea because the point is to go fast.

And then, when all the testing is done, the ship and the Shipyard part ways. Time to go to work on the next one.